A New Golden Age: The Secret Letters of Mary Queen of Scots

AI is aiding codebreaking, but humans still matter more

Before we get on to the main subject, here’s an intrusive exclusive News Alert:

I have a new book coming out on May 20 called . . . Phantom Fleet: The Hunt for Nazi Submarine U-505 and World War II's Most Daring Heist. The clue to the subject is cunningly concealed within the title. You can read more about it via this link.

Or you can click this enticing picture to pre-order it (these things really do matter to authors, you know):

Alright, with that out of the way, let’s begin . . .

You probably don’t know it, but you’re living in a Golden Age of historical cryptography. Over the last decade or so, researchers have been breaking, at an astounding rate, codes and ciphers that have lain, frustratingly unreadable, in various archives for centuries. At last count, the total cracked stood at around 2,500.

In so doing, they’ve revealed any number of secrets about the past and shed new light on episodes hitherto cast in shadow. I’ve discussed one or two of them in earlier posts (see “Reading Maximilian’s Mail” below), but today I’m finally getting around to covering possibly the greatest penetration of all: a top-grade cipher used by Mary Queen of Scots (1542-1587), Catholic claimant to Elizabeth I’s throne.

This is actually the second Golden Age of reading stuff that once couldn’t be read. The first occurred in the early 19th century, when Champollion used the Rosetta Stone to crack Egyptian hieroglyphics and Grotefend broke Old Persian cuneiform. They did it with masterly philological skill and maximum linguistic brainpower, but nowadays scholars have turned to computers and, more recently, AI, to speed the process. But still, human wisdom and experience often count for more. The brilliant flash of insight, one might say, is more powerful than the tedious clanking of gears.

It’s also much more collaborative than in Days of Yore. The lone genius simply can’t do it all anymore. So the way the pipeline generally works is: (1) researchers convert the archival document into a series of digital images; (2) computational linguists turn those images into machine-readable text, a difficult job given that the very rarity and wide range of handwritten coded symbols hinders AI from “guessing” their meaning (though this aspect is rapidly improving); (3) cryptanalysts employ statistical analysis, clustering, simulated annealing, hill-climbing, heuristics, and other tricks that I obviously don’t really understand to come up with likely solutions to the puzzle by gradually reconstructing the (lost) key used by the original encipherers; and, finally, (4) bring in the historians to explain the context and significance of the message.

To that end, there were three experts involved in the Mary case: Satoshi Tomokiyo, a Japanese physicist and cipher enthusiast; Norbert Biermann, a German musician and cryptanalyst; and George Lasry, a computer scientist in Israel with long experience of cracking historical codes.

While working in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Tomokiyo found a cache of 57 encrypted letters, all written with a quill on handmade paper. Their provenance was unknown; so too was their date (though the writing resembled a late sixteenth-century hand), their subject, their recipient, or their sender. Not even the original language was certain: For a time it was assumed to be Italian or Latin.

Challenged by this worthy puzzle, the enterprising trio set about solving it. A big breakthrough came a few days later when, hypothesizing from the few scraps they had, they realized that the sender was an imprisoned woman using an older form of French. After a lot of painstaking work and numerous dead ends—it didn’t help that there were numerous ciphering errors by the scribe—the pieces slowly began to fall into place as each mysterious symbol was revealed—no fewer than 219 of them.

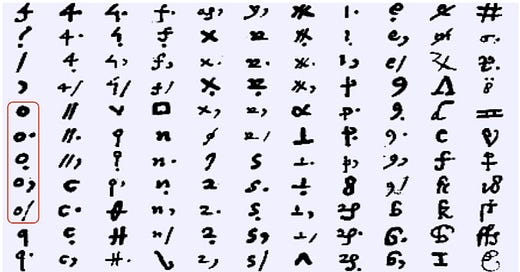

The cipher was an impressive one: This was expert-level encryption, filled with homophones (multiple symbols used to represent the same letter), diacritics (accent-style marks attached to symbols to indicate a given word or part of it so that W, W/, and W. meant different things—see photo above, outlined in red), nulls (blank letters to reduce the risk of frequency analysis), and a lengthy nomenclatur (a dictionary of symbols attributing key names, dates, and places). Since diacritics weren’t in common use until the 17th century, the cipher was at least 25 years ahead of its time.

It turned out that the haul was the secret correspondence of Mary herself between 1578 and 1584, encrypted from her verbal dictation by her private secretaries, then smuggled out of her prison and couriered to Michel de Castelnau Mauvissiere, the French ambassador in London, who passed each letter to Paris.

Mary relied on three of these secretaries for her system. The senior one was Claude Nau of France; the middle-ranking on was the Scot Gilbert Curle; and the junior, a young Frenchman named Jérôme Pasquier. As cover, Nau served as Mary’s foreign minister of sorts, Curle specialized in Scottish affairs as domestic adviser, while Pasquier was her master of the wardrobe and almost certainly her originating connection to Castelnau: Either he or his father had once been his secretary.

An English report on Nau and Curle amusingly noted that the dour Scot, apparently conforming to national stereotype, “is not so quick spryted nor prompt as Nau (French-like), but hath a shrewd melancholy wit, not so pleasant in speech & utterance.” Pasquier was unknown to, or at least unsuspected by, Sir Francis Walsingham—Elizabeth’s famous spymaster, who was obsessed with Mary—but in fact he seems to have been the key man for the Queen’s cipher efforts. It was he who performed the laborious work of enciphering and deciphering, though it was Nau who handled Mary’s French dictation (Curle was the English translator when necessary) and safeguarded the cipher keys.

All of these much-rumored letters had long been presumed lost, but they together—all 50,000 words’ worth—filled in much of the murky backstory of the years leading up to the queen’s execution. As Professor John Guy, a leading authority on the subject, put it, this collection of letters was “the most important new find on Mary Queen of Scots for 100 years.”

A full analysis of the meaning and significance of their contents awaits a (or “an”—I’m one of these weirdos who persists with “an”) historian. If you’d like to try your hand, Lasry and his co-authors have published the abstracts in the journal Cryptologia, including the complete text of several letters. Not being a Tudor specialist, I’ll freely confess that I’m at sea with most of it, but what I find most interesting—speaking as the author of Spionage—is what can be gleaned about Mary’s use of cryptography.

What is immediately obvious, for example, is that Mary was an adept of ciphers: When her rooms were later searched, more than a hundred cipher keys were discovered (but not, obviously, the one she used with Castelnau). She was also exceedingly, and rather sensibly, cautious. Perpetually wary of Walsingham’s spies, she would initially employ a “nursery” cipher—an easily penetrated one comprising basic alphanumeric and symbolic substitutions—to test new couriers and potential agents. Since these letters contained only chickenfeed and harmless gossip, if they betrayed her Walsingham would end up wasting his time with her “What lovely weather we’re having” musings.

Only once their loyalty had been demonstrated by long and faithful service would Mary “[command] a more ample alphabet to be made for you, which herewith you will receive.” These more “ample alphabets” were tougher and more conspiratorial “mature” versions employing trigrams (three-letter sequences), digraphs (pairs of letters making a single sound), longer nomenclaturs, more nulls, and so forth.

Perhaps most interesting, or most tragic, is that in the end her excellent security practices did her no good. What got her, as it does so many other spies down the ages, was ironically not the code—because they never intercepted this set of letters,Walsingham’s decipherers never broke the Castelnau version—but human error, fear, and weakness.

Frustrated that he had nothing self-evidently damnable on paper, Walsingham switched strategies to focus on penetrating her network with doubles and informants. In mid-1583, he succeeding in compromising Mary’s channel to Castelnau when his agent, aliased Fagot, “made the ambassador’s secretary my friend [so] that, if he is given a certain amount of money, he will let me know everything he does, including everything to do with the Queen of Scots.”

Who this treacherous friend was remains uncertain (it was either Claude de Courcelles, Castelnau’s secretary, or Laurent Feron, a clerk Fagot bumped up to secretary to impress Walsingham). Mary, however, soon realized that someone was leaking from the Castelnau end and shut down the link. The ambassador was recalled home in 1584, bringing to an end this set of correspondence.

Two years later, Walsingham managed again, this time more successfully, to infiltrate Mary’s communications by entrapping her in the Babington Plot using a double agent named Gilbert Gifford to forward her correspondence. Still, nothing in the decrypted texts was enough to condemn her, legally speaking, because Mary disclaimed any knowledge or involvement in this conspiracy to assassinate Elizabeth. She had not, after all, enciphered her own letters and there was nothing written in her hand giving her consent.

The fatal blow was ultimately the testimony of Nau and Curle (Pasquier claimed he couldn’t remember any of the letters’ contents), who were promised their lives in exchange for their swearing that the queen had approved of the plan to murder Elizabeth and had ordered them to encipher her go-ahead (“proceed in the [rest of the] enterprise”).

At that point, then, cipher or no cipher, Mary was doomed and she was beheaded on February 8, 1587.

Further Reading:

N. Akkerman and P. Langman, Spycraft: Tricks and Tools of the Dangerous Trade from Elizabeth I to the Restoration (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024), esp. Chp. 2; N. Biermann, S. Tomokiyo, and G. Lasry, “What Encryption Errors Can Reveal: Cross-Cipher Errors in Mary Queen of Scots’ Letters,” Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Historical Cryptology; J. Bossy, Under The Molehill: An Elizabethan Spy Story (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001); M. Héder, A. Fornés, N. Kopal, F. Szigeti, and B. Megyesi, “Supporting Historical Cryptology: The Decrypt Pipeline,” Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Historical Cryptology; G. Lasry, N. Biermann, and S. Tomokiyo, “Deciphering Mary Stuart’s lost letters from 1578-1584,” Cryptologia, 47 (2023), 2, pp. 101-202.