It's Good To Be The King

An Indian Treatise on Spying That Makes Machiavelli's Prince Look Like a Kid's Book

In 1905, a Sanskrit scholar named Dr. Rudrapatnam Shamashastry was in the Mysore Oriental Library sifting through dusty stacks of palm-leaf manuscripts when he stumbled across the literary equivalent of Tutankhamun’s tomb: A single copy of a fabled text, missing for seven centuries.

It was the Arthashastra, a 4th-century BC work written by Kautilya, the National Security Adviser, Chancellor, and Prime Minister (to give him modern titles) to the founder of one of the greatest of all empires, ancient and modern alike. As Hand of the King, to put it in Game of Thrones terms, Kautilya had composed his treatise to teach Chandragupta Maurya and his dynastic successors the “science of politics”—a loose translation of “Arthashastra.”

A more accurate version would be, “science of political economy,” for it’s a guide to running a prosperous and ordered state—though that stuff’s not what attracts readers, of which there are unfortunately few in the West, where the book is hardly known.

No, the material that is most interesting—at least to Secret Worlds subscribers, that most literate, sophisticated, and civilized of Substack audiences—is the Arthashastra’s obsession with cloaks, daggers, spookery, and surveillance.

Wolf to Man

Little concrete is known of Kautilya, but he seems to have compiled the Arthashastra from the works of at least fourteen older or contemporary sources on politics and kingship, including passages in the Hindu holy text, the Mahabharata.

Given the impressive library Kautilya drew upon, I think we can safely say that his India was a place where man was wolf to man. They must have needed all those manuals, let’s put it that way.

Following Alexander the Great’s death (323 BC), his generals divided up his empire, whose once-boundless borders had finally come to a halt in northern India, when his exhausted troops had been confronted by the likelihood of battle with the mighty Nanda dynasty. Facing an army of fresh infantry and cavalry, one fortified by war-elephants and four-horse chariots, they had mutinied, forcing the conqueror of the world to withdraw from India, soon after to die.

Though wealthy and well-armed, the Nanda dynasty was unpopular with its subjects, making it ripe for overthrow. A young, domineering Chandragupta Maurya (born circa 350 BC)—sources conflict whether he was the son of a Nanda concubine or from a humble background—was mentored by the older Kautilya (born 375 or so), who may have been a priest or teacher, and together they ousted the last of the Nanda kings around 321 BC. The Arthashastra is thought to date between the time of Chandragupta’s seizure of the throne and 300, five years before his death.

Together, Chandragupta and Kautilya remorselessly expanded the Maurya domain from their (or rather, the late Nandas’ ) capital of Pataliputra in north-eastern India, at the confluence of the Ganges and Son rivers.

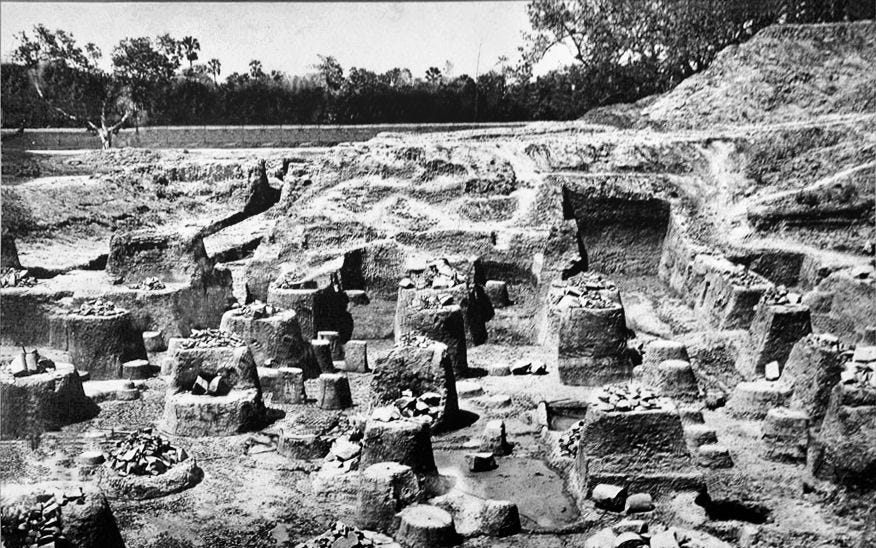

Patalipatra was a remarkable city, possibly the largest in the world. Megasthenes, a Greek ambassador of Seleucus I (one of Alexander’s generals and founder of Persia’s Seleucid Empire), recorded that it was a parallelogram in shape, with wooden walls extending ten miles on their longest sides and nearly two on their shortest, and pierced by 64 gates. Aside from its natural riverine defenses, there were 570 towers studding the palisades and a ditch 600 feet wide to the landward side.

Dozens, scores of petty kingdoms, strange and fierce fiefdoms, and obese satrapies fell into their hands as the Mauryan Empire spread across northern India. Chandragupta’s defeat of the Seleucid forces in 303 BC, followed by a marriage alliance with his former enemies and a gift of 500 elephants, brought his western frontier all the way to what is now Kandahar in Pakistan.

The World of War

Yet never there was peace in this world of war. Peace was not the alternative to war, only planning for the next war was. Here, a mighty king did not arm himself to secure peace through a balance of power, only to conquer those naive enough to ask for negotiations. There was no justice, except that dispensed by the sword, only ruthless, ceaseless calculations of strength and weakness. If you saw a chance to hurt a foe or undermine a friend, take it—because he would do the same to you.

Which is where Kautilya came in. He added his own distinctive gloss to the stack of How To Be A King manuals he’d amassed. As a man who considered murdering rivals, poisoning enemies, and framing foes as everyday practice—to be fair, it probably is if one is engaged in his line of work—Kautilya’s volume can be likened to a mixture of Machiavelli’s The Prince and Sun Tzu’s Art of War.

But only “likened.” Really, there’s nothing else like Kautilya. The Art of War’s focus, for instance, is on martial matters, with an occasional mention of the need for intelligence. Sun Tzu, unhelpfully, doesn’t tell budding warmongers how to spy, though, he just says they should do it. Kautilya, on the other hand, holds nothing back in explaining the headspinning number of ways one can spy the daylights out of everyone.

The Man From M.A.U.R.Y.A.

Kautilya relates that there are at least 29 cover occupations for spies. Among his favorites are to disguise them as wandering monks, traveling bards, jugglers, tramps, herdsmen, mendicants, soothsayers, sorcerers, servants, thieves, lunatics, buffoons, the deaf or dumb, vintners, bakers, butchers, and rice-cookers. He was also a fan of using “the hump-backed dwarf, the eunuch, and women of accomplishment” as sources.

Their task was to circulate propaganda and glean rumors among the village and town populations, to try to incite unrest to test loyalty, to report on local administrators’ probity, and to generally keep an eye out for anyone suddenly spending money lavishly, acting suspiciously, getting wounds treated secretly, or ignoring caste restrictions. New arrivals of “condemnable character,” like actors and dancers, were of particular interest.

Other spies, the real pros, were to be employed for specific missions. Some were sent to poison rival kings, liquidate treacherous ministers, and execute other disruptive operations. An excellent way of getting someone else to do the dirty work and deflecting suspicion from oneself, notes Kautilya, is for an agent to approach the brother of a suspected traitor and propose that he kill him to gain his estate; once done, this Cain would then be executed on a charge of fratricide.

In speaking so openly, Kautilya’s a hundred times more expansive than the Florentine demon, Machiavelli. The latter existed in a Catholic Christian world where honest discussion of assassination, spies, and torture—all popular pursuits in Renaissance Italy—was frowned upon and he himself wistfully exalted the glories of republican Rome as a moral exemplar for the various Medicis and Borgias. Despite his malevolent reputation, Machiavelli was an idealist at heart.

Kautilya wasn’t. There was no golden age to which he harked, and neither had he to heed Christian precepts, so he was happy to say the quiet part out loud—if only because his master needed to hear it so he could protect his subjects from others’ predations. All very worthy, even idealist in its own clear-eyed way.

Government by Espionage

Nevertheless, one does occasionally get the impression that Kautilya, co-enabled by Chandragupta, might have just been a paranoiac militarist who saw conspiracies, betrayals, and sedition everywhere. There’s a story that Chandragupta was so worried by the threat of assassination that he slept in a different bed every night—a story which, if true, would certainly give us an insight into the bizarre nature of his court.

According to Kautilya, the king was expected to devote no less than a third of his scheduled twelve daily hours of work to intelligence matters. From around midday, ninety minutes was dedicated to reading reports from spies; after sunset, he interviewed spies for another hour and a half; and finally, after midnight he sent spies on their missions.

That doesn’t even count how much time the king had to spend protecting himself against the intrigues of his own ministers and officials, including the high priests, “the heir-apparent, the door-keepers, the officer in charge of the harem, the magistrate, the collector-general [of taxes], the chamberlain, the commissioners, the city constable, . . . heads of departments, the commissary-general, and officers in charge of fortifications [and] boundaries.”

Any one of them could be planning to usurp him, after all. Kautilya advised setting up a system to stress-test their loyalty.

Fire your chief general occasionally, then see if he attempts to recruit other officers to join him in trying to oust you, ran one rule. Bribes, ostensibly from foreign potentates, were freely offered to officials to induce them to turn their coats. Other times, his entire cabinet should be jailed on trumped-up charges to confirm who would try to foment discord among them.

Those who passed the test received preferment, but Kautilya, being a worldly fellow who understood all men were fallible, believed that those who failed should only be posted away from the court and demoted to running outlying towns, mines, elephant-training facilities, and forests where they could do no harm. Why kill these otherwise competent, if weak, retainers?

The exception was a man who succumbed to lust during a test in which a provocateur would whisper to the target that the queen fancied him and wanted to put him on the throne. For him, there could be no mercy. His fate was to be cooked alive in a large jar.

The 4th-century society described in the Arthashastra, one has to admit, does seem to resemble the total surveillance state of post-war East Germany, but I don’t think that’s truly the case. For one thing, Chandragupta’s empire was both less centralized and more sprawling than East Germany, making total surveillance impossible.

For another, oftentimes Kautilya’s “spies” are not spies as we conceive of them, but are instead officials of the vast bureaucracy that ran his socialized monarchy. Their jobs were to compile reports from hearsay, observations, and tips to guard against local corruption, to evaluate what is now called “public opinion” in the provinces in order to redress grievances before they became problems, and to ensure timely tax payments from perhaps recalcitrant landowners.

Kautilya and the Greeks

Even with all that in mind, Kautilya’s security apparatus and his vision of intelligence-gathering was a wonder to behold, at least from the historian’s point of view. In a previous post—have a read below—which discussed espionage in ancient Greece, I briefly mentioned the Arthashastra and how sophisticated it was compared to contemporaneous Greek practice.

To take one example, Greek intelligence-gathering was always hampered by their faith in oracles, magic, and omens, but Kautilya has no time for any of that mummery. Believe in Science, he advises—not science as we know it, but his Science of Politics—for only that, not astrology, will guarantee success in his world. “The object slips away from the foolish person who continuously consults the stars … What will the stars do?”

But the best bit, so typical of Kautilya, is adding that a king should nevertheless exploit the superstitious nature of the people by paying fraudulent holy men to prophesize that his reign is divinely ordained and that those who wish for riches and happiness must be loyal subjects.

His most advanced insight, I think, is his emphasis on cross-referencing the flurry of contradictory or incomplete reports arriving from agents. George Washington would later be a master of this technique—I discuss it in Washington’s Spies—but Kautilya beat him by two-thousand years.

Spying was, or is, a field often inhabited by fantasists, flatterers, and adventurers, and no wise case-officer completely trusts a report until it can be verified independently in order to weed out exaggerations, self-puffery, and inaccuracies. Thanks to his huge network of operatives, Kautilya was able to insist that no fewer than three sources must agree before information would be judged sound. If only two were valid, more agents would be sent to elicit additional intelligence, and if his sources habitually conflicted then that meant that at least one was a double or deceitful.

I wouldn’t rate that guy’s chances for surviving the night.

Kautilya’s Trees

The great question is, how long did Kautilya’s government-by-espionage last? Did Chandragupta’s successors rule according to the Arthashastra’s precepts? Given how complex and all-encompassing his system was, it’s doubtful it survived much beyond his and Chandragupta’s lifetimes.

We know very little about Chandragupta’s son and heir Bindusara, so that’s difficult to ascertain, but we do know a lot about his remarkably enlightened and beneficent grandson, Ashoka the Great (c. 268-232 BC), who ruled over a truly golden age of spiritual purity, social harmony, and imperial prosperity.

As a kind of Buddhist Edward the Confessor, he declared at the outset that he would reign morally on the principle of dharma—upright conduct, duty, piety, and justice. Granted, every ruler in history has said the same upon his or her accession, but Ashoka may well have purposefully rejected the ethos and practice of Kautilyaism to better reflect the new spirit of his age.

Kautilya was a product of his times and environment. It was a tough neighborhood, where one was either the bully or the bullied, and it was the bully whose rule brought order and stability. That Greek proverb comes to mind about a society growing great when old men plant trees in whose shade they shall never sit.

Kautilya would have shuddered at Ashoka’s apparent naivety, but he may have been the one who planted the trees in the first place.

Further Reading: R. Shamasastry, Kautilya’s Arthashastra (Mysore: Mysore Printing and Publishing House, 3rd edn., 1929); R. Boesche, “Moderate Machiavelli? Contrasting The Prince with the Arthashastra of Kautilya,” Critical Horizons, 3 (2002), 2, pp. 253-76; Boesche, “Kautilya’s Arthashastra on War and Diplomacy in Ancient India,” Journal of Military History, 67 (2003), 1, pp. 9-37; P.H.J. Davies, “The Original Surveillance State: Kautilya’s Arthashastra and Government by Espionage in Classical India,” in Davies and K.C. Gustafson (eds.), Intelligence Elsewhere: Spies and Espionage Outside the Anglosphere (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2013), pp. 49-66.

I downloaded Arthashastra to my Kindle. This should be fun!