Untold numbers of letters, papers, and diaries today sit unread in the world’s archives. It’s not for want of trying: Scholars have attempted to read them for centuries. It’s that they can’t be read—because they’re ciphered and no one knows how to read them. Occasionally, though, researchers enjoy a victory, mostly thanks to the power of modern computers and a remarkable proficiency in linguistics and philology.

A recent example is the breaking of three diplomatic letters composed in 1575 by the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II. The plaintext was then encrypted by the imperial chancellery before being sent to Habsburg officials in Poland.

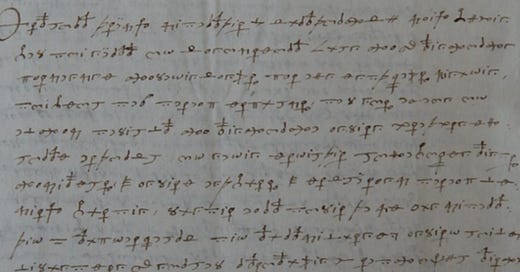

They were a tough nut to crack. The first two are no fewer than eight or nine pages long and contain between 7,300 and 9,500 ciphertext symbols; the third is short, just a few pages with 1,600 symbols. These symbols consist of astrological-style signs, Greek letters, and esoteric marking.

First on the agenda was to work out what language the cipher was enciphering. The Holy Roman Emperorship was a multinational, polyglot organization, so the original letters could have been composed, say, in diplomatic French or aristocratic Spanish or the universal standard, Latin.

It would turn out to be German—or more specifically, Early New High German written in a stiff, ornate chancery style beholden to an abiding love of subordinate clauses—the kind of tone one would expect from the mandarins of the Habsburg imperial chancellery.

Easing the task of decryption was that the clerk had a good, clear hand to simplify transcription and, because cryptological security at the time was in its infancy (though improving fast), the chancellery made two elementary errors.

First, the same key—the dictionary listing each symbol’s meaning—was used for all three letters. Crack one, then, and you get everything. Through sound archival work, computer scientist Nils Kopal and linguist Michelle Waldispühl eventually managed to locate the matching key in a different folder from where the letters were kept. It was named Cyffra Nova Ad Poloniam and was developed in 1572, just three years before the letters were sent. Three years is an eternity in modern cryptography, but by contemporary standards it was a pretty top-tier, up-to-date cipher specifically invented, as its name indicates, for the emperor’s Polish business.

Ultimately, though, having the key was more helpful than critical, as Kopal and Waldispühl had already deciphered 80 percent of the first letter using a specialized software called CrypTool 2 before even finding the key. With it, they were able to increase decryption to 95 percent, the rest possibly being clerical mistakes or one-time references to places or people.

The second error was to leave telltale spaces between words, to rely on the same ciphertext symbol for several common pairs of letters or even a whole word like und (and), and to often leave an umlaut (ä, ö, ü) in the cipher where it would otherwise be in the plaintext. Taken together, these slips made it quite simple to detect frequently used words like der and das, or to figure out umlauted common ones like trägt.

Still, the cipher had a few tricks up its sleeve. For instance, there were some nulls, or fake symbols, cleverly inserted to throw off any nosey parker who might have intercepted a letter. The hashmarks in the image below are all nulls to obscure the emperor’s identity.

So what do they say, these letters? When supplemented by two other encrypted letters sent to the emperor some time earlier by a Lithuanian nobleman named Johan Chodkiewicz—also broken by Kopal and Waldispühl—they reveal the machinations surrounding the election of a new Polish king and Grand Duke of Lithuania to replace the former king, Henri of Valois, who had traded up to the French throne in mid-1574.

In most places, crowns were passed by dint of heredity, but that of what was then the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was different: Some 50,000 nobles were to gather in Warsaw on November 7, 1575 and vote for the next king.

Soon after Henri had scarpered for Paris, Chodkiewicz had tipped off Maximilian that the Poles and the Lithuanians were split as to their favored candidate. The emperor, he suggested, should send envoys to Lithuania to grease the skids and ease the path if he was interested in securing the vacant throne.

Maximilian was certainly interested and wanted his candidate—himself, of course—to prevail in the coming election to secure Habsburg influence. Aside from gratifyingly adding to his existing titles of King of Bohemia, King of Germany, and King of Hungary and Croatia, being King of Poland would be a useful geopolitical hedge against the ever-present threat of Russia.

Maximilian then began to secretly concert his efforts with the friendly Marshal of Lithuania, Prince Nicholas Radziwiłł, to bring the hostile Polish noble faction to his side. There was some talk of bribes to persuade any Polish holdouts of the justness of the Habsburg suit over the local favorite, Princess Anna Jagiellon and her ambitious consort Stefan Báthory, Prince of Transylvania.

Using Radziwiłł as a middleman was probably a Chodkiewicz idea. He appears to have cautioned against Maximilian directly exercising his influence, if you know what I mean, as it might lead to “all sorts of repulsive thoughts [and] all kinds of confusions” among the higher-minded lords. Better to let one’s allies on the ground do the heavy lifting.

By December 1575, Maximilian’s scheme had half-worked. The nobles, still divided, had plumped for a double election: Both Maximilian and Stefan had been awarded the crown and victory depended on who got to Kraków first to claim it.

The Holy Roman Emperor was clearly annoyed and considered it beneath a Habsburg’s dignity to race to Poland at the behest of a bunch of mere nobles. In the end, Maximilian mulled going to war over the matter, but died soon after Stefan and Anna were crowned on May 1, 1576.

Generally speaking, the letters are by no means a revelation: The diplomatic struggle between Maximilian and Stefan over the Polish crown is well-known. But, like all secret intelligences, they allow us a tantalizing glimpse into how sausages get made.

Further Reading: N. Kopal and M. Waldispühl, “Deciphering Three Diplomatic Letters Sent by Maximilian II in 1575,” Cryptologia 46 (2022), No. 2, pp. 103-127; Kopal and Waldispühl, “Two Encrypted Diplomatic Letters Sent by Jan Chodkiewicz to Emperor Maximilian II in 1574-1575,” in C. Dahlia (ed.), Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Historical Cryptology (Sweden: Linköping University Press, 2022), pp. 80-89.