In 1999, when Wilhelm Höttl died, few people paid attention. He’d led a quiet life since the mid-1960s running a private school, his bourgeois existence interrupted only by the occasional swindle, such as when his school went bankrupt, but not before its coffers had been emptied with conveniently precise timing.

For anyone unfortunate enough to be familiar with the good Herr Doktor (he was very particular about his title), that was par for the course. Höttl, you see, had long enjoyed an unfortunate reputation, justly, for general shiftiness and sharp practice.

Among intelligence services, he had once been infamous. Indeed, his CIA file, at 1,600 pages, is one of the most voluminous kept on former SS officers, and understandably so. This was a man who had worked, after all, for not only the Sicherheitsdienst (SD)—the SS’s intelligence and domestic-security branch, later integrated into Reinhard Heydrich’s Reich Security Main Office (RSHA)—the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the U.S. Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC), the West German Defense Ministry, and, for good measure, the KGB. Oh, and don’t forget the Yugoslavian UDBA and French SDECE. It was quite the record.

Above all, he was a charmer, so charming, in fact, that his colleague Adolf Eichmann once incautiously confided to him late in the War that he estimated “six million Jews” had been murdered. When Höttl later recounted this in testimony against his former pals at Nuremberg, it was the first time anyone had heard that number bruited and it was entered into the official record.

Alas, that may have been one of the few truthful things Höttl ever said. His was a life of duplicity and mendacity, and the fact that he kept being employed as an agent provides a lesson in why intelligence services should be wary of getting into bed with terrible people, no matter how “valuable” their intelligence is claimed to be—usually by those selfsame terrible people.

The Early Years

Höttl, the son of an Austrian civil servant, was always dodgy. Born in Vienna in 1915, he was an early convert to Nazism, joined the Hitler Youth at 16, and the SS in 1933, aged 18, when it was illegal in Austria. He was soon working as an informant for the SD. In 1937, he acquired a doctorate in history from the University of Vienna and joined the SD soon afterwards, specializing in Jewish and Masonic affairs because he was an intelekshul.

In December 1940 he was promoted into the intelligence department of the Vienna SD office. His avarice and corruption were soon the talk of headquarters. Confiscated Jewish assets and large sums of money from SD accounts would vanish into his capacious pocket. His boss, SS-Sturmbannführer Friedrich Polte, who perceptively considered him “a liar, a toady, a schemer, and a pronounced operator,” appealed to Berlin and Höttl was sent to the Eastern Front in 1942 as a Waffen-SS war correspondent while the investigation rolled on.

There he might have stayed, and died, had it not been for the appointment of his fellow Austrian, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, as the head of the RSHA in January 1943 after Heydrich’s assassination in Prague. Kaltenbrunner, who’d known Höttl since the 1930s, needed allies, preferably Austrian, within the RSHA to counter the sway his German rival Walter Schellenberg (chief of SD foreign intelligence) had with Heinrich Himmler.

The once-doghoused Höttl did fabulously well thanks to these office politics. Invited back to Berlin, he became an Italy specialist and participated in the rescue of Mussolini in September 1943. Hitler himself acknowledged his role and Höttl’s promotion to SS-Sturmbannführer (the equivalent of a major), despite his not having reached the requisite age of 30, was assured.

The following year, Kaltenbrunner transferred him to Budapest to help establish a Nazified government that would assist Eichmann to liquidate the country’s Jews. Höttl never condescended to get his hands dirty, of course, and was far-sighted enough to make sure, in an almost-plausibly deniable way, as having no tangible involvement in the deportation of some 400,000 Hungarian Jews to Birkenau in April-June 1944.

The End of the War

Like many senior officers, Höttl could see the writing on the wall by early 1945 and made an effort to save himself from the noose by talking secretly to the advancing Americans. A number of meetings ensued with Allen Dulles, the OSS chief in Switzerland, with Höttl claiming to be an envoy from Kaltenbrunner and Himmler to discuss the possibility of a peace deal.

To buy himself protection, Höttl exaggerated the danger of the so-called “Alpine Redoubt,” where Hitler was rumored to be amassing a horde of SS fanatics to wreak havoc as stay-behind saboteurs.

It wouldn’t be the last time that Höttl touted himself as an apparently invaluable source with high-grade intelligence thanks to his mysteriously uncontactable but powerful connections.

He certainly convinced Dulles the Alpine Redoubt was a reality, though it ultimately turned out to be nothing more than a fever dream. Otherwise, Dulles wasn’t quite as a wide-eyed as Höttl believed. He was aware that, as he put it, Höttl’s “record as a SD man and collaborator of Kaltenbrunner is of course bad and information supplied by him is to be viewed with caution.” Even so, and here Dulles cited what would become the conventional wisdom concerning Höttl, he still “may be useful.”

In truth, Höttl was playing the Americans along. He managed to avoid being tainted with evidence of war crimes by claiming that his father was Karl Höttl, an Austrian socialist and school-reform advocate (he wasn’t related), and that all along he had been an anti-Nazi quietly working within the system to help his fellow Catholics. He repeatedly asserted that he had not been involved in any crimes and pretended that his exile to the Eastern Front had been prompted not by his enthusiastic theft of Jewish property but by Heydrich’s suspicion that he was simply too sympathetic to the Jews for his own good.

During his interviews, the strategy—and this was the case with every leading Nazi—was to blame someone else, preferably a dead superior, for all the diabolical stuff while manfully accepting just enough responsibility for minor things to avoid scepticism in one’s proclaimed innocence.

So, he would admit that he had “heard talk” of killings of “Communists” in the East, but then assure his questioners that he had had no hand in these murders. After that, tearful expressions of sorrow for his guilt in not having done more to save the poor innocents, followed by a demonstration of a hearty willingness to bring to justice those who had disgraced Germany, worked their magic on the more naive interrogators.

With The New Breed

Despite his best efforts, Höttl had a tough time in the immediate aftermath of the War. That was because his American interrogators tended to be Jews who’d been forced to leave Germany in the 1930s. Like Avner Less, Eichmann’s future interrogator in Jerusalem, they knew Germans—they were German themselves, of course—and were familiar with what had really happened.

It was difficult, then, Höttl to pull the wool over their eyes, and they had known perfectly well that an old-time SD man like Höttl, especially one with his murderous reputation in Hungary and his palliness with Kaltenbrunner and Eichmann, was hardly likely to be Mr. Pro-Semite. To add insult to injury, they referred to him contemptuously as “Höttl,” and refused to address him as Herr Höttl, let alone Doktor Höttl—an exquisite insult in Germany, akin to calling the President “bro.”

Their scepticism about Höttl’s motives and excuses kept him on the be-very-cautious watchlist, but by 1946-47 this original cadre had left and been replaced by a new breed of younger Americans working for the Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) who didn’t speak the language and didn’t understand the German mentalité, but who were very alarmed by the threat of Communism. Ex-Nazis like Höttl impressed them with the seeming depth of their knowledge about the mysterious Soviets. To them, he was, respectfully, Herr Doktor Höttl.

As Höttl unctuously told his gullible prospective employers, because he felt he could be “of considerable benefit to the interests of the USA,” he had “voluntarily reported to the U.S. Army” rather than attempt to flee. As one “who has never acted against the principles of international law and morals,” he had nothing to hide and so much to offer.

Thomas Lucid, Chief of Upper Austria for CIC, was an easy mark. Höttl quickly gleaned that Lucid would take everything he said at face value. Höttl “has proven to be an excellent source for ideas . . . on the expansion of American intelligence in Austria,” enthused Lucid in a report. His experience as one of Heydrich’s and Kaltenbrunner’s men—a good thing now, apparently—“enables him to evaluate incoming reports on the Soviets with fairly complete accuracy.”

Lucid was so impressed that he agreed to fund a number of intelligence networks in Austria, Hungary, Romania, and Ukraine that would be run by Höttl. The latter claimed that he could reactivate his old wartime nets and deliver inside intelligence on Soviet designs. Among Höttl’s well-placed agents were an oil foreman, a leading lawyer, a chief engineer, a wholesaler, a railroad official, a secretary in Vienna for the Cominform (a Communist organization in nine European countries), an interpreter at Red Army headquarters in Germany, and a senior member of the Communist Party.

An extraordinary collection of agents, it seems. One wonders whether any of them actually existed—elsewhere but in Höttl’s fertile imagination, that is. What is beyond doubt is that all the money Lucid earmarked for Höttl’s networks inexplicably disappeared while his reports got thinner with every recycling.

Meanwhile, ever more suspicions about Höttl were piling up, not that Lucid paid heed. Höttl’s former secretary said her boss was “not a man to be completely trusted”; interrogators’ notes highlighted both his dark past and his dubious associates; and a CIA officer who knew Höttl well viewed him as “a born intriguer and dyed-in-the-wool Austrian Nazi.” This last one was particularly percipient in adding that he “wouldn’t rule out that Dr. Höttl, on purely opportunistic grounds, might decide to play ball with the Russians.”

It was only in the summer of 1949 that Lucid was finally persuaded to drop Höttl—and only then because his star spy was seen cavorting with at least four known Soviet penetration agents and the British accused him of betraying one of their men to the Russians. Worse, perhaps, a CIC investigation revealed that information Höttl had sold them was “deliberate deception aimed at misleading American intelligence.” (It probably didn’t make them feel any better, but Höttl later enterprisingly resold those reports to French Intelligence.)

Sidenote—Thomas Lucid

Lucid went on to join CIA, where he helped major Nazi war criminals escape via Italy to South America, as exposed in Philippe Sands’s The Ratline, and later ran agents from Saigon, where he was essentially The Quiet American, just a lot less competent than even the hapless protagonist of Graham Greene’s novel.

Another interesting thing: As Sands discovered, Lucid’s illegitimate son married the daughter of one of his other agents, that agent being SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Hass (died 2004), a mass executioner of Jews and Italian resistance fighters.

One should never gainsay the course of true love, obviously, but Lucid’s closeness to his Nazi contacts raises the question of whether he was a controller being controlled by Höttl, Hass, & Co., or whether he was more politically and religiously sympatico than one should expect in an American intelligence officer, or if his anti-Communism blinded him to the sins of his sources.

He died in 1985, never knowing that Hass, his fellow dad, had also been working for the Soviets.

Exposure

Now at a loose end, Höttl spent the next few years trying to squirm his way into the West German intelligence service. He was more an annoyance than a threat, at least until January 1953, when American authorities in Vienna arrested two Soviet spies (both had served in U.S. Intelligence during the War) named Kurt Ponger and Walter Verber. They had been watched since 1949, but one name stood out in the reports: A Wilhelm Höttl had been seen on several occasions meeting them in strange places like highway rest stops.

Höttl was hauled in for questioning, but the canny old SD man denied everything and claimed that all he’d been doing was discussing potential journalistic projects with the other two. CIC Special Agent Rolf Ringer was the lead interrogator and had to give up because:

“When faced with the two alternatives that he was a witting member of the Soviet-controlled [Ponger] complex or that he was a complete dope, Höttl refused to accept either alternative. Being a proud man, he argued at length against the accusation that he must have been a fool to be taken in by Ponger and at the same time maintained that he never in any way tumbled to the true affiliations of the Verber-Ponger family although he was aware that the Pongers resided [in] the Soviet sector of Vienna.”

Further, he was “determined to hold out under heavy pressure and appear ridiculous if necessary, rather than yield one inch of the story he has prepared.”

By sticking to his cockamamie tale, Höttl was demonstrating prime-grade anti-interrogation tradecraft, preventing anyone from being absolutely certain that he was working for the Soviets and aware that Ponger/Verber were under Moscow control. The CIA estimated there was at least a 90 percent chance he was guilty on both counts, but it couldn’t be proven.

The other 10 percent, suggested an evaluator, could be that Höttl was being set up to be recruited later as a mole, possibly after joining West German intelligence. Even so, when Höttl proposed to run himself back against the Soviets as a double, the CIA turned him down: His reputation had long preceded him. “All readers of this report will be overwhelmed with relief,” one official concluded, “that the interrogator did not accept Höttl’s offer.”

(If you’re curious, yes, Höttl was guilty as sin. Two KGB defectors in the early 1960s confirmed that he had been “a Soviet agent of long standing,” as well as being one of the highest paid. At hearing this, one CIA Chief of Station chortled that if the well-remunerated Höttl had been one of theirs then it meant he’d defrauded Moscow along with everyone else.)

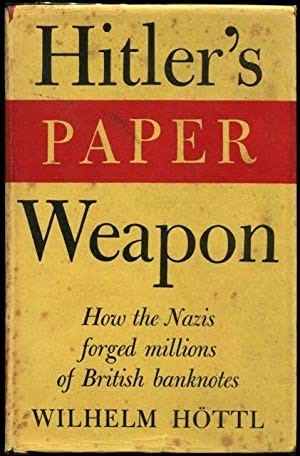

After the Ponger-Verber episode, a now permanently burned Höttl retired from the spy trade and established a school (the one he ripped off). He also wrote a self-serving book or two, including a so-called history of the German effort to counterfeit British banknotes and his made-up memoirs. Occasionally, he’d be invited onto a television news show to pose as an intelligence expert. His Nazi past, of course, was never mentioned.

Only once did he get a scare, and that was when Hungary demanded his extradition on charges of murdering resisters and deporting Jews, but the Austrian government, as part of its creative “We Were Innocent Victims of Hitler, Too” policy, refused the request.

He died peacefully in 1999, aged 84.

The Bigger Picture

Wilhelm Höttl was by no means unique. More than a dozen other Nazi war criminals had a thumb placed on the scale for them by CIC—an organization dedicated to hunting down, er, Nazi war criminals. The most notorious of these toxic assets was Klaus Barbie, the “Butcher of Lyons,” who served as a CIC informant (“an extremely valuable source”) until his mass-murderous past came to be regarded as too outré for continued employment. Even then, he was spirited away to Bolivia.

The CIC’s rationale was that since other countries were using war criminals as spies and informants too, the United States couldn’t afford to be picky. CIC could also point out that at the time it didn’t have definite knowledge of the depth and depravity of its sources’ crimes. Morever, the policy was legal in the sense that CIC had been ordered to arrest all war criminals with the exception of those deemed potentially useful for intelligence purposes—a loophole people like Höttl fully exploited.

Even so, in the immediate aftermath of the War suspects were granted little leeway and less mercy. Members of the SD, SS, and Gestapo were in the “automatic arrest” category, and in 1945 the CIC, for instance, arrested some 120,000 Germans in just seven months on suspicion of Nazi Party membership or war crimes.

What changed to Höttl’s benefit was the swing away from fears of a Nazi revival to the need to combat Communism in late 1946 and 1947, culminating in the Soviet takeover of Czechoslovakia and blockade of Berlin in 1948 and the first nuclear experiment in 1949. As the USSR was a closed society, signals intelligence was almost impossible to acquire, leaving human agents the sole recourse.

Starved of information, CIC personnel looked around and saw that the most staunchly anti-Communist people around were former Reich security officers. Many of them had the language skills and the necessary experience in Eastern Europe that would allow them to pass on to their American patrons the kind of deep, arcane knowledge of the Reds they were so desperately seeking.

The smarter ones like Höttl instantly understood that you could erase your embarrassing Nazi past so long as you trumpeted your anti-Communism to dolts like Thomas Lucid. Make sure, too, to keep schtumm about the anti-Semitism while talking up the virtues of democracy. (The ones who couldn’t bear to lose the anti-Semitism, like Eichmann’s right-hand man SS-Hauptsturmführer Alois Brunner, tended to exile themselves to Egypt and Syria, where it was still cool, and over time became pro-Soviet.)

Who Was Höttl?

The interesting thing about Höttl, unlike most of the others, is that’s difficult to discern exactly what he believed—at any time.

Was he a servant of convenience, opportunistically spouting whatever the existing regime expected in order to enrich himself? A nasty little peddler of intelligence scraps and invented “insights”? An adventurer only out for himself?

Or was he a convinced Nazi all along, who believed, like many others in his circle, that the USSR and the US were equally bad and that German power could be restored by maintaining a neutrality between East and West?

Either explanation can fit his willingness to work for the KGB, which both paid well and could be used as a lever against CIA in the hopes they would mutually destroy each other, ultimately benefiting Höttl as much as Germany.

If I had to say, it was the former. The unceasing lies, the charming bluster, the recycling of low-grade alarmist “intelligence,” the rush to expose his ersatz soul to suckers to gain their trust, a willingness to betray old comrades, and the illimitable enthusiasm to work for literally anyone who paid him bespeak a world-class con artist, not a 6-D chess genius playing the Americans and the Soviets against each other to create the Fourth Reich.

In the end, though, what matters is that while people working for the good guys like Lucid admittedly had to treat with Nazis, like it or not, they forgot that when dealing with the lesser of two evils—in this case a helpful former Nazi as opposed to the major criminals like Eichmann—they were still dealing with evil.

Further Reading: P. Biddiscombe, Werwolf!: The History of the National Socialist Guerrilla Movement, 1944-1946 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998); T. Boghardt, “America’s Secret Vanguard: U.S. Army Intelligence Operations in Germany, 1944-1947,” Studies in Intelligence, 57 (2013), 2, pp. 1-14; T. Boghardt, “Dirty Work?: The Use of Nazi Informants by U.S. Army Intelligence in Postwar Europe,” Journal of Military History, 79 (2015), pp. 387-422; N.J.W. Goda, “The Nazi Peddler: Wilhelm Höttl and Allied Intelligence,” in R. Breitman, N.J.W. Goda, T.J. Naftali, and R. Wolfe, U.S. Intelligence and the Nazis (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005); T.J. Naftali, “Creating the Myth of the Alpenfestung: Allied Intelligence and the Collapse of the Nazi State,” Contemporary Austrian Studies, 5 (1996), pp. 203-56; D. Orbach, Fugitives: A History of Nazi Mercenaries During the Cold War (New York: Pegasus Books, 2022); P. Sands, The Ratline: Love, Lies, and Justice on the Trail of a Nazi Fugitive (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2020); M .Wala, “Stay-Behind Operations, Former Members of SS and Wehrmacht, and American Intelligence Services in Early Cold War Germany,” Journal of Intelligence History, 15 (2016), 2, pp. 71-79. David Kahn interviewed Höttl in 1972, and left an oddly sympathetic recollection. Höttl’s testimony for the Eichmann Trial can be read here.