If there’s one thing we all know Casanova (1725-98) for, it’s that he was The World’s Greatest Lover™. His very name’s eponymous with profitable amatory endeavor. Not so much talked about is that he was also a busy spy and informer for the Venetian Secret Service.

The reason we know so much about his (exaggerated) Pick-Up Artistry and so little of his intelligence career is that that’s how he wanted it.

Casanova’s memoirs, Histoire de ma vie, composed in late age, linger over his love life, but skim lightly over his work as a spy. It’s barely mentioned, in fact—a little odd, surely, given his incessant boasting and waspish delight in intrigue.

There’s a curious parallel here with the members of the Culper Ring, which served George Washington during the War of Independence—contemporaneous with Casanova’s spying activities.

In my book, Washington’s Spies, I pointed out that in Benjamin Tallmadge’s own 68-page memoirs, written half a century after his Culper days, he devotes precisely three sentences to his intelligence work:

“This year [1778] I opened a private correspondence with some persons in New York [for General Washington] which lasted through the war. How beneficial it was to the Commander-in-Chief is evidenced by his continuing the same to the close of the war. I kept one or more boats continually employed in crossing the Sound on this business.”

Neither did any other member of the Ring speak about his involvement afterwards. Now, one might ascribe their reticence to the natural modesty of good, middle-class men in rural Long Island, but that does not explain why such a monster of conceit as Casanova equally kept, as the Psalmist said, his mouth as a bridle.

For modern audiences perhaps more accustomed to spooks blowing the gaff in books and articles as soon as they leave the secret world, we need to ask, Why So Silent?

Early Lives

By the time he was 30, Giacomo Casanova had already led several lives. Born into a Venetian acting family (his real father may have been a nobleman), he was raised by his grandmother, who recognized the lad’s quick wits, high intelligence, and talent for social mimicry. Casanova would always claim to have blue blood, and even if he didn’t, he certainly knew how to masquerade as one.

He went to the University of Padua (aged 12) and graduated five years later as an ecclesiastical lawyer. For a short time, he even entered holy orders, but was invited to leave the Church following a love tryst—the first of many such scandals.

Thereafter, he drifted into the Venetian Army, not exactly a martial powerhouse, but the bright white uniforms groaning under the weight of their gold epaulettes were impressive. Casanova bragged in his Memoirs that he looked spectacular in his, and that all the ladies agreed.

His military career didn’t last long. He gambled away not only his pay playing faro, but also the money he received from selling his officer’s commission. Aged 21 now, he turned his hand to becoming a theatre violinist, his fellow musicians being among the most degraded and louche fellows he ever encountered. Casanova enjoyed his time getting beastly drunk and playing practical jokes (“we amused ourselves by untying the gondolas moored before private homes”), but, always the chancer, he grasped his opportunity with both hands when it arrived.

Following a wedding ball, he was traveling with the aged Senator Matteo Bragadin in a gondola when the patrician suffered a minor stroke or heart palpitation. Casanova leapt into action and resuscitated him through a combination of medical guesswork, mumbo-jumbo, and luck. The senator was convinced that the young man possessed occult powers and esoteric forbidden knowledge—Casanova did not disabuse him of this useful belief—and became his mentor, patron, and almoner.

After a few years with Bragadin opening doors for him in Venice, Casanova embarked on a foreign tour. Beginning in 1750, he mooched and sponged and shagged his way across Europe. Paris was, of course, his favorite city (“imposters and charlatans can thrive better [there] than elsewhere”), but he was spotted at the gambling tables and in sundry countesses’ beds in Prague, Dresden, and Vienna. In 1753, he was back in Venice, where he opened his own faro house.

That’s when things began to go wrong.

The Lions’ Mouths

Eighteenth-century Venice was Las Vegas on the Lido. Its courtesans were as famous, or as notorious, as its masked Carnival, and its risque theatres existed cheek-by-jowl with its opulent gambling hells. It was the most anticipated stop on the Grand Tour for young gentlemen all too eager to spend their stipends on acquiring a different form of knowledge than that so hopefully intended by their parents.

Yet Venice, in a manner similar to that of Nevada’s Sin City, where prostitution is illegal and gambling is politely referred to as “gaming,” had an incongruously puritanical side. More than two hundred years earlier, in 1539, a three-man body called the State Inquisitors had been founded. It was a domestic counter-intelligence and anti-subversion department (as opposed to the Consiglio dei Diece, the Council of Ten, which was its MI6/CIA counterpart, and the Inquisition, which dealt with religious matters).

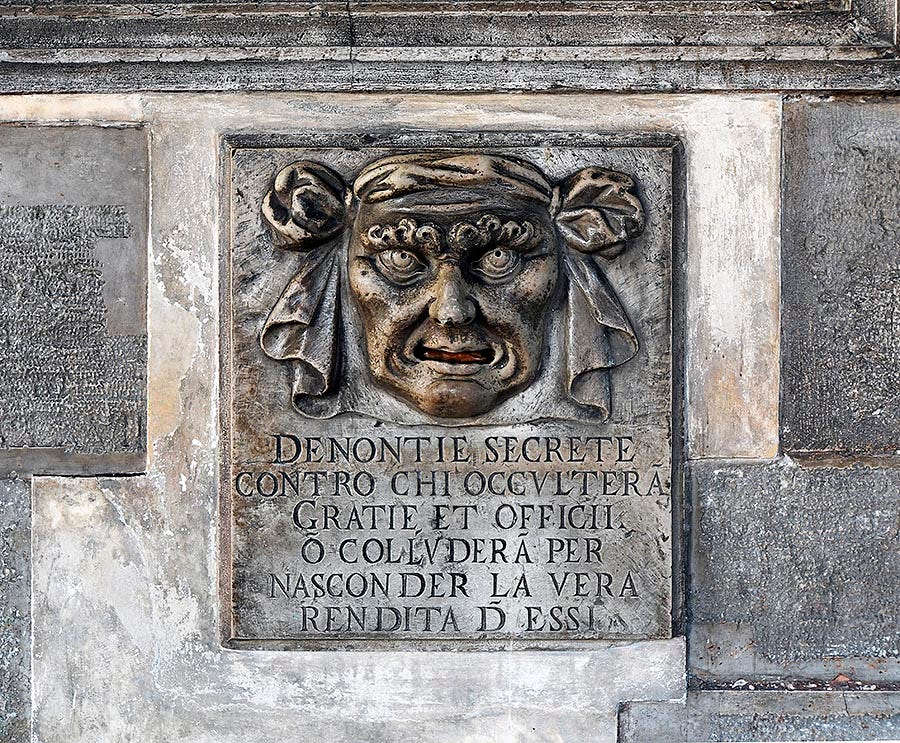

The State Inquisitors encouraged a culture of snitching, denunciation, and informing. Such had been the origins of the famous Bocche di Leone (Lions’ Mouths) around the city, which were postboxes into which people could insert letters attesting to others’ crimes. These were then brought to the State Inquisitors, where they were read, evaluated, and eventually filed in Venice’s extraordinary archives.

Thousands of these complaints are extant today, allowing us a unique view into a centuries-old surveillance operation. Informers would hang around coffee houses, hotels, theatres, and marketplaces watching for breaches of etiquette, impertinent remarks, heckling, surreptitious assignations, strangely worded sermons, neighbor quarrels, price-gouging, congregants flirting in church, and conduct unbecoming noble rank, such as buying rounds in taverns and other indications of general shadiness.

Consorting with prostitutes was always a popular sin to report, as was homosexuality, coarse remarks about the government, electoral corruption, being too “clever” (i.e., interested in foreign ideas), cardsharping, brawling, and practising alchemy.

In those lovingly catalogued and cross-referenced archives live the records of all the variety and diversity of our splendid species, and while they make for fascinating reading the visiting Mark Twain professed to be horrified by the malevolence of the Lions’ Mouths:

These were the throats, down which went the anonymous accusation, thrust in secretly at dead of night by an enemy, that doomed many an innocent man to walk the Bridge of Sighs and descend into the dungeon which none entered and hoped to see the sun again.

Oh, it wasn’t as bad as all that. Twain was exaggerating. In reality, in the overwhelming majority of cases the State Inquisitors did nothing. That was because they were less interested in scandalous gossip than in finding instances of political and religious dissent—the really dangerous stuff. Freethinkers, Jacobins, atheists, blasphemers, Enlighteners, Rosicrucians, Freemasons, and the like were what truly exercised them.

And that’s what would bag Casanova, not the other peccadillos.

Casanova’s File

An informer named Giambattista Manuzzi submitted numerous reports on Casanova to the State Inquisitors between November 1754 and July 1755. These are lodged in the archives, and it’s interesting to watch Manuzzi up the ante to bring in his target.

At first, Manuzzi’s intel was chickenfeed, consisting primarily of plain-jane observations. Casanova was, for instance, “a writer but of a fertile and scheming cast of mind” who produced spiteful satires, lived off others, and cheated at cards. (All accurate, by the way.)

Manuzzi kept digging until in July he found gold. Casanova was a Master Mason, and almost as bad, he had made disparaging remarks about the Virgin Birth to his drinking pals. “Those who believe in Jesus Christ are very deficient in their wits,” Manuzzi cited him as saying.

Those comments, and perhaps also an ill-advised attempt to seduce a nun, provoked an arrest order from the State Inquisitors. A couple of weeks later, on the night of July 26-27, 1755, Casanova was taken to the Piombi in the Doge’s Palace for interrogation. These were the famous “Leads,” so named because they were cells for political prisoners located under the lead roof.

It wasn’t particularly uncomfortable there, but he was too splendid a bird to be caged. After a year, he plotted an entertaining escape, described in his Memoirs, and went on the run to Paris. The State Inquisitors subsequently forbade him from entering Venice.

Back in the Good Books

For nearly 20 years, Casanova traveled around Europe, indulging in the usual libertinism and amassing debts he could ill-afford to ever repay.

Throughout his exile, Casanova tried to curry favor with the Venetian authorities to allow him to come back home. His imprecations were ignored, but he seized a chance in November 1772 to remove the black mark next to his name when he pitched up in Trieste, desperate and penniless, and offered his services to the Venetian consul, Marco Monti. As it happened, Monti had a job for him.

To make a convoluted and quite operatic story short, Casanova paid off a Habsburg official to prevent a breakaway faction of Armenian monks, who’d scarpered to Trieste from the Venetian monastery of San Lazzaro, from establishing a rival print works to the one in Venice. The Armenians, threatened by an excommunication from one of Casanova’s friends, gave up and returned to Venice.

Everyone was a winner, aside from the Armenians, but the best news was that Monti recommended to the State Inquisitors that Casanova’s banishment be revoked. In September 1774, Casanova was at last home.

Casanova the Spy

But this Venice was not his Venice. Two decades had passed and his toadies and cronies had aged or died, leaving Casanova without connections and income. It was then, in December 1774, that the hard-up libertine approached the State Inquisitors for employment as an informer-spy.

The response was lukewarm, to put it mildly. Casanova first had to prove his utility to the state, they answered. The Trieste Job had been a good start, but they needed more proof of his loyalty.

Consequently, Casanova submitted numerous reports during 1775. None were too explosive—two noblemen had scuffled over a mistress, he had witnessed gambling in brothels, and a lawyer had uttered seditious remarks about the law—but they were sufficiently satisfactory to persuade the State Inquisitors to hire him as a part-time informant in February 1776 under the alias “Antonio Parolini.”

Casonova/Parolini initially specialized in immorality affairs: corruption among ecclesiastical lawyers, suspiciously easy marriage annulments, a masque called Ballo di Coriolano which sowed “in susceptible minds a certain spirit of rebellion,” that kind of thing.

A short time later, he branched out into foreign intelligence, the purvey of the Council of Ten and a distinct step-up. Back in Trieste he discovered that the Austrians were secretly improving the harbor at Fiume to prepare for a possible invasion of Dalmatia, while the Papal consul was illicitly financing the recruitment of mercenaries for the King of Prussia. Not too shabby, concluded his masters.

On October 3, 1780, Casanova was promoted to confidente attuale—an officially employed spy with a monthly salary of 15 ducats, with the possibility of a pension for continuing good service. Cock-a-hoop about being back in the money, Casanova promised that he would bring in scoops by the dozen, but went on a spending spree instead and subsequently submitted only dribs and drabs concerning the activities of “whores and rent-boys” in theatre boxes.

After only three months, the State Inquisitors cancelled his contract and put him back on a freelance, piecework basis. The financial constraints improved his performance, which was perhaps the intention, as he now had to scramble for scraps. He soon discovered an illicit printing-press run by a Spaniard, a bawdy theatre hidden in the Hospital of the Mendicant Order, a naked model at the academy of painting, and an olive-oil smuggling scheme.

Casanova’s biggest coup came on December 22, 1781, when he tracked down a supply of “licentious books” (some by Voltaire and Rousseau, and others by atheists like Spinoza), and a cache of erotic texts “deliberately written to excite with filthy voluptuous tales the waning and languid desires we must defy,” as he piously put it. These had been smuggled into Venice and were being fenced through booksellers, and were exactly what the State Inquisitors were looking for (the licentious books, not the porn).

Just as Casanova was re-ingratiating himself to them, he managed to blow it the following year by publishing a libelous pamphlet concerning two noblemen of his acquaintance. Threatened with another involuntary stay in the Piombi, he fled Venice.

Again, he drifted across Europe for the next few years, but he was by now an aging, rouged roué who’d long since exceeded his welcome and his credit line. He was also turning increasingly reactionary and pious, putting him out of step with the revolutionary Enlightenment spirit threatening to blast through France.

A few years later he at last grasped that he was a man out of his time and accepted an appointment as librarian to Count Karl von Waldstein, chamberlain to Emperor Joseph II, at the dismal, lonely castle of Dux in Bohemia. At least it gave him the time to write his memoirs.

Which brings us back to the question asked at the beginning. Why did he remain so quiet about his time in the secret world?

The Ambo-Dexters

To understand his reasoning, keep in mind that in the eighteenth century there were essentially three types of spies.

The first kind operated within the aristocratic confines of Europe’s palaces and chancelleries. Ambassadors picked up intelligence and gossip from various throned dynasts and their generals, writing it down and sending a report home in code. Before they left, these reports would be, in a ritual as stiffly formalized as Kabuki, be unsealed and decrypted, then replaced, by the host country’s so-called Black Chamber. Since everyone expected his or her mail to be read, the really secret stuff had to wait until the ambassador returned home.

A second form of spying is better described as military reconnaissance. Officers would be sent out on missions to probe enemy lines, sketch fortifications, and map the lay of the land. This was the most ancient form of espionage, and could claim a pedigree harking back at least to Moses, who despatched twelve Israelites to, as the Bible says, “spy out the land” of Canaan. Similar accounts can be found in the works of Homer, Thucydides, and Julius Caesar.

And the last was practised by lowborn blackguards and desperadoes who insinuated themselves into better society in order to, as a disgusted Voltaire once put it, “sell friends’ secrets and earn their living by informing and often by calumny.”

Swarming the underworld and infesting the underbelly of Europe as the lice and frogs did Egypt, they served as agents provocateurs, and infiltrated (or invented) plots against the government. These operatives were rarely ideologically or religiously inclined and sought instead reward or preferment. As one clear-eyed Bavarian instruction noted in 1773, “without money one does not get far” with these fellows.

They were sometimes dubbed “ambo-dexters,” as they changed sides with enviable ease. Understandably, they bestowed upon the practice of espionage an unsavory reputation. The playwright Ben Jonson amusingly captured the prevailing image and pathetic fates of these creatures:

Spies, you are lights in state, but of base stuffe,

Who, when you have burnt your selves down to the snuffe,

Stinke, and are throwne away. End faire enough.

As you may have gathered, it was this third type of spying in which Casanova was forced to specialize—a humiliating descent for a magnifico who had once streaked like a comet across the firmament.

Over in America, the perceived ignobility of spying was what led the members of the Culper Ring to disclaim any role in it. I remember reading one of their letters in which the farmer Abraham Woodhull, who could have done with the money, was mortified that General Washington offered to pay him for his services.

Getting repaid their expenses, yes, that was a given, but for Woodhull to accept money meant that he had become an ambo-dexter, a light of base stuff. He was insulted to have been offered money, but was equally embarrassed that Washington had offered it in the first place, for it implied that the general did not regard him as an honorable gentleman. (Washington took the hint and never brought up the matter again.)

You can see now why Tallmadge, an upstanding Yale man and Continental Army officer, kept his activities on the down-low, and why Casanova tried to do the same when he first approached Consul Monti in Trieste in 1774 about undertaking secret work for the Republic.

In his supplication, he pleads that the consul “please remember that one of my major concerns has to be that no one in this city ever manages to find out that I am one of your secret agents.” He had two reasons to insist on discretion. First, as a practical matter because if it became known he would be blown as a source, but more important was the second: “I would risk being driven out in disgrace, a fatal misfortune for my poor honor.”

Indeed, in his Memoirs, while Casanova frequently mentions other spies, he echoes the Culpers’ revulsion and contemporary opinion in describing them as as a “disgusting brood,” “scoundrels,” “vile,” and so on.

Casanova returned to the subject in 1788, by which time he was working as a librarian and reconciling with the Lord for a lifetime of mischief and dissipation.

His newfound Catholicism, and his tormented sense of ruefulness over lost virtue, emerges in a painfully honest line that he omitted from his Memoirs but included in his novel, The Icosameron, Or The Story of Edward and Elizabeth, a rather strange bit of early science-fiction.

Spies, he wrote, were men of “good repute [who wished] the world to be unaware that their trade is to betray: It is punishment enough for them to know it themselves.”

Further Reading: D. Chambers and B. Pullan (eds.), Venice: A Documentary History, 1450-1630 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001); J.C. Davis (ed.), Pursuit of Power: Venetian Ambassadors’ Reports on Turkey, France, and Spain in the Age of Philip II, 1560-1600 (New York: Harper & Row, 1970); F. De Vivo, “Ordering the Archive in Early Modern Venice (1400-1650),” Archival Science, 10 (2010), 3, pp. 231-48; U. Franzoi, The Prisons of the Doge’s Palace in Venice (Milan: Electa, 1997); P. Preto, Spie e Servizi Segreti della Serennissima (Venice: Biblioteca dei Leoni, 2017); P. Preto, “Giacomo Casanova and the Venetian Inquisitors: A Domestic Espionage System in Action in Eighteenth-Century Europe,” in D. Szechi (ed.), The Dangerous Trade: Spies, Spymasters, and the Making of Europe (Dundee [U.K.]: Dundee University Press, 2010), pp. 139-56; P. Preto, I Servizi Segreti di Venezia (Milan: Saggiatore, 1994), S.P. Winchell, “The CDX: The Council of Ten and Intelligence in the Lion Republic," International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 19 (2006), 2, pp. 335-55.

I really enjoyed reading your article, thanks so much for sharing. Great bibliography too.