The Search for Szek

The Greatest Spy of the Great War Vanishes Without Trace, or Did He?

In 1915, a young Belgian spy named Alexander Szek disappeared after handing over to the British Secret Service a painstaking copy of the most secret German codebook. He was never seen again.

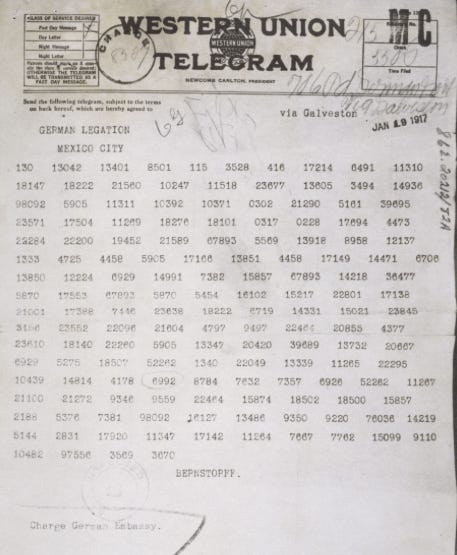

The book contained the keys to decrypting Berlin’s military and government ciphers, and it was owing to Szek’s bravery that the famous, enciphered Zimmermann Telegram would later be cracked by the British.

In it, Arthur Zimmermann, the German Foreign Minister, would propose to the Mexicans on January 16, 1917 that they ally with Berlin once the latter initiated unrestricted submarine warfare. In return for an invasion of the southwest, Germany would aid Mexico to regain Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.

After intercepting the Telegram, the British passed the decrypted version to Washington. Once the newspapers got hold of the revelation on March 1, it was only a matter of time before the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, ensuring its doom.

Owing to its world-historical consequences, the decrypted Zimmermann Telegram was one of the most fateful intelligence documents of all time. As the man who provided the key to its solution, Alexander Szek can thus justly lay claim to being the most important spy of the First World War.

So, why haven’t you ever heard of him?

The Szek Story

Szek wasn’t always obscure. Partly due to his D.B. Cooper-like disappearance, in the 1920s and 1930s he was a well-known figure. Sightings and speculations regularly cropped up in the press beneath headlines like “Greatest Spy Mystery,” and he was much ballyhooed in the Great War spy memoirs of the time.

Thrilling wartime tales of SOE and OSS exploits pushed him into the background in the 1950s, but by the 1960s and throughout the 1980s Szek was again being mentioned in histories of MI6 and the like. Since then, Szek has vanished yet again, which make this an excellent time to reopen the case.

What I’ve done here is compile a kind of Ur-version of the Szek story based on H.R. Berndorff’s 1930 book, Espionage (which I’ve discussed in this post), Robert Boucard’s entertaining Revelations From the Secret Service (1930), and Henry Landau’s too-often overlooked Spreading the Spy Net, published in 1938.

There are, of course, discrepancies between the accounts—Berndorff was German, Boucard French, and Landau South African/British, so they adopted different perspectives on the matter—but I’ve reconciled them as best I can to smooth out the story.

The Background

In 1914, following the German invasion of Belgium, officers billetted to the mansion of a wealthy, well-connected Austrian businessman named Josef Szek were surprised to find that the man’s son, Alexander, was a keen radio hobbyist who had devised a receiver more advanced than anything the Army was using.

German military intelligence immediately recruited him to monitor wireless transmissions at their Brussels station. As part of his duties, he was entrusted with the highest-grade communications between the government, its ambassadors, and the General Staff, all sent by the most secret code.

This code was contained in two volumes, one thick and one thin, the first containing an alphanumeric substitution chart (i.e., a word was expressed as a number, similar to the system employed by the Culper Ring and described in Washington’s Spies), and the second, a table outlining a daily change to the numbers to preserve confidentiality.

Despite being subject to conscription into the German Army, Szek remained a civilian and was assigned a private room, his job being to decipher the telegrams and dispatches that went in and out of headquarters.

In early 1915, pleased to discover that Szek’s mother Elisabeth was English, that he had been born in a London suburb in 1894, and that he had discreet connections to the Belgian resistance, a longtime British naval-intelligence officer, one Captain Trench, sought to enlist him into secret service. To help Szek make the right decision, Trench handed him a message from his mother patriotically imploring him to work for the British.

Interlude

Trench is one of those extraordinary fellows who tends to pop up in the secret world. He was actually Bernard Trench, a former Royal Marines officer in his 30s, who’d been arrested for espionage in Germany a few years before the War. He’d been released in 1913 as part of a diplomatic deal when the Kaiser pardoned him. When the War broke out, Wilhelm’s generosity was not reciprocated and Trench, probably obscured as “Agent H.523” by Landau, went back to his old ways of spying the daylights out of the Huns. He died in 1967.

Now, Szek was deathly afraid, but Trench persisted and eventually his new recruit agreed to make a copy of the codebooks. Each night, he would surreptitiously reproduce a couple of pages of each volume and sneak them out.

Once his task was completed in late 1915, Trench asked him for the documents, but Szek seems to have held on to them as security. His luck had recently run out and he’d been summoned for military service on the Front. Szek wanted out, and he’d only give over the code if Trench exfiltrated him to Britain.

Trench warned him that as soon as the Germans discovered him gone they’d change their codes, but Szek countered that he’d already taken that into account. He’d acquired a medical pass certifying that his nerves needed a rest and he would be unmissed by his colleagues for some time. Against his better judgement, but unable to do anything else, Trench accompanied Szek to the Dutch-Belgian border so they could cross the eight-foot-high electric fence, guarded by sentries, separating the two countries.

Now trusting Trench, Szek handed over the code and together they waited for their chance on a moonless night. But a police dog started barking, the searchlights switched on, and sentries rushed towards where they were crouching in the high grass.

Trench, being an old hand at this sort of thing, was wearing rubber gloves and managed to get through the fence without being zapped. He eventually squired the papers back to London, where they would be used by the Admiralty’s Room 40 codebreakers to crack the Zimmermann Telegram in early 1917.

Szek’s Fate

What happened to Szek is where things get murky. Based on information from Szek’s father, Josef, Berndorff and Boucard claimed that Alexander had in fact also successfully crossed the Dutch border but that a British agent had murdered him as they traveled to Britain on a ferry. His body was shoved overboard.

The reason, Berndorff explained, was that had Szek “continued to live he might, in a weak moment, during the course of the war, have revealed the fact that he had stolen the code for the British Government,” rendering it useless. So, Reginald Hall, the Director of Naval Intelligence, had cold-heartedly ordered his assassination, presumably by Trench.

Josef Szek kept the case in the public eye after the War. Boucard’s Revelations stated that Szek senior had amassed a folderful of documents and had shared them with him. As Berndorff put it, the “father expended large sums of money and employed private detectives in his endeavors to find his son.” He even wrote a “despairing letter to [Hall], imploring Hall to tell him what had become of his son. Sir Reginald Hall replied that he had never heard the name of Alexander Szek.”

In 1930, Josef added more mystery to the tale by saying that he had recently received a letter in his son’s handwriting—only that the signature was under a different name. Obviously, Alexander was still alive and in hiding somewhere in Britain. No wonder Hall had claimed ignorance! He was protecting his ace of spies from the vengeful hand of German assassins in the spook equivalent of the Witness Protection Program.

Just before World War Two, Henry Landau muddied the waters more by hinting strongly that Alexander had been captured and killed back in 1915 in Belgium. I may cover Landau in a future post, but for the time being it should suffice to say that he had been recruited by MI1c (later renamed MI6) to run a network of agents in Belgium and France distinct from Naval Intelligence’s. After the 1918 Armistice, he was on the Military Intelligence Commission in Brussels, where he was charged with shutting down the wartime networks.

As part of his job, Landau had looked into the Szek matter and interviewed “a former German soldier who had served during the War as a warder.” This man said that Szek had been caught at the frontier and was “kept in solitary confinement in the Namur prison, that he was tried by court-martial, found guilty of being a deserter from military service, and shot.”

Still, even Landau remained unsure whether Szek had really died. He could find no record of his death and Szek’s father had not been informed of the outcome. All most unusual . . .

Josef Szek dismissed Landau’s claim as typical British propaganda to cover their tracks, and since the latter’s book had been published in America—old spies liked to avoid British libel laws by being published there—it did not receive much publicity at home.

So it became the Received Version that Naval Intelligence agents had murdered Szek in the English Channel to preserve the mother of all secrets. Now, this was partly because it contained all the sexiest elements of spy skulduggery, but also because the British themselves believed it added to their cultivated mystique of being the World’s Greatest Intelligence Professionals.

In several subsequent books, the story was accordingly repeated without question while new details were added. Colonel Edward Calthrop, MI6’s head of station in Brussels between the Wars, said in the 1950s he’d heard that Szek was “accidentally” hit by a car by Naval Intelligence agents to keep him quiet. And Admiral Oliver, a former head of Naval Intelligence, was quoted as boasting, “I paid £1,000 to have that man shot.”

As late as 1984, Professor M.R.D. Foot—the eminent Official Historian of Britain’s Special Operations Executive in the Second World War—confirmed privately to Michael Occleshaw, an expert on British military intel, that Szek had been murdered on the ferry and his body dumped overboard.

Now, if anyone would know about such dark deeds, it would have been Foot with his deep contacts within British Intelligence and his familiarity with the relevant archives. To all intents and purposes, then, the Search for Szek had come to an end.

But it hadn’t. In fact, it had never really begun.

The Telegram

Let’s start digging a bit into the story. The first thing you need to know is that any claims regarding Szek’s involvement in the decryption of the Zimmermann Telegram are utter twaddle. He had zero to do with it.

How the Telegram was cracked is a complicated story, but in a nutshell the cryptanalytical breakthrough was done entirely in-house by the Admiralty boffins in Room 40.

In other words, no top-level German codebooks were used as cheat sheets—not that a low-level civilian employee stationed in Brussels could even dream of having access to them in the first place. And even if Szek had possessed such an Open Sesame security clearance, and had made copies, surely someone in Germany would have changed the codes at some point between his mysterious disappearance in October 1915 and the transmission of the Zimmermann Telegram in January 1917?

To that point, the Zimmermann version of the code was introduced only in late 1916, so how on earth did a wireless clerk get a hold of it a year earlier?

Speaking of weird inconsistencies, here are some others. Decryption and encryption of messages, especially anything above medium-grade, did not take place in Brussels, but in Berlin—so why would Szek possess such classified codebooks? Further, the German Foreign Ministry never used any other transmitter for sensitive material but the giant, high-powered, secure one at Nauen, far far away from Szek in Brussels.

In any case, why would Berlin be sending top-secret telegrams to Mexico through Brussels anyway?

At the time, the British had cut the Atlantic cables connecting Germany with the United States, forcing Berlin to convey messages to its embassy in Washington via then-neutral U.S. State Department diplomatic cables. The British, in fact, came across the enciphered Zimmermann Telegram by “intercepting” (to put it politely) these secret communications as they passed through London. Brussels was never part of this diplomatic traffic.

The Truth

With that in mind, we can safely surmise that while young Szek was entrusted with some basic radio codes—the kind of codes the French had broken within a month of the war’s outbreak—his real value would have been his familiarity with the German order of battle: regimental designations, unit positions, troop strengths, organization, that sort of thing.

It was boring stuff that was considered priceless by pros like Landau and Trench. The former, for instance, once paid a German deserter no less than a £100 for the Field Post Directory he brought with him.

So it was Szek’s knowledge, not his code access, that made him a tempting target for recruitment. What Trench hadn’t counted on was that Szek wanted out, he was desperate to avoid military service, and so did not want to remain in place—where he would have been useful. That Szek had received call-up papers forced Trench’s hand and he had to bring him over, especially since his agent was smart enough to hold back much of the material to ensure a payout and protection.

What happened next, I’m afraid, is woefully uncinematic. On October 15, 1915, Alexander’s mother, who was a German resident in Brussels (not English and living in Britain, as usually stated), went to the Austrian legation to plead with officials to intervene with the German Governor-General to release her son from custody. (Alexander was Austrian through his Hungarian father and was a British subject through birth, but potentially subject to conscription through his mother.)

She returned several times, anxious about Alexander. It was to no avail. The sparse records, which were discovered by John Maclaren and Nicholas Hiley in 1989, note that on December 5, Szek was tried by a military court; the next day, he was listed as a “sentenced prisoner.”

On December 10, convicted of evading military service and (probably) being caught carrying secret papers, Alexander Szek was executed by firing squad and his body was unceremoniously thrown into an unmarked grave behind the barracks of the military prison in which he was held.

The Myth

Yet one question remains. How did this obscure deserter become one of the greatest spies of the age? The answer lies with his father, Josef.

Josef was actually a more intriguing character than his unfortunate son. No matter what he later said, of course he knew Alexander had been shot in mid-December 1915, but the boy served his purposes.

Josef’s record, you see, was not spotless and he desperately needed to clean up some stains. During the War, for instance, as a fervent German nationalist, he had worked enthusiastically for the occupiers in a counter-espionage role. He snitched on suspected Allied sympathizers, confiscated 800 Belgian radio sets, and undertook such dirty-tricks work as infiltrating resistance organizations.

Or so he said. At the Austrian Foreign Office, Josef Szek was a well-known loon. One official noted that he was “an elegant talker and verbalist who tried to convey the impression that he was a genius.” In short, Josef Szek exhibited all the telltale signs of being a fantasist and conman with a dark side.

Still, there’s evidence to show that Szek had worked in some capacity for German intelligene, and certainly enough for him to be worried about what would happen after the Armistice, when ex-enemy aliens like him were apt to be arrested and tried by the Belgians. He must have been worried, too, about his property and estate being seized as reparations.

In 1920, Szek tried to buy goodwill by informing on an Urban Vessen, a prison guard during the War now posing as a monk and serving as a German political-police agent. From then onwards, Josef Szek busily constructed a new identity as a stout Belgian patriot and, to help fix his story, he alchemized Alexander Szek from anonymous traitor into the brave Belgian superspy of legend.

Szek subsequently sold the story to credulous “intelligence experts” like Berndorff and Boucard, as well as to various gullible reporters, who amplified the late Alexander’s modest exploits by adding lashings and dollops of make-believe and sensationalized spookery.

The only person who comes out of this well is Henry Landau, who seems to have been right on the money, not that anyone believed him, when he wrote that he’d interviewed one of Alexander Szek’s prison guards. (One wonders whether his source was Urban Vessen.)

History Rhymes

We’ve been here before, you know. In my earlier post on John Honeyman, the completely fake spy of the American Revolution, quite a similar thing happened.

Real life was not exciting enough for some, and there were dubious wartime records to expunge, so a heroic back-story was conjured up by relatives for their own benefit once the “spy” was dead. I suspect this happens more often than we’d like to think in the secret world.

It rarely does the culprit much good—the last we hear of Josef is his being busted for fare-dodging on a Belgian tram in 1935, which sounds about right—but the vivid by-product of their fantasies toxically live on for decades (or centuries, in Honeyman’s case) in popular books, articles, and film.

The truth is always right there, though. You just have to look at the documents.

Further Reading:

H.R. Berndorrf (trans. B. Miall), Espionage (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1930); R. Boucard (trans. R. Somerset), Revelations from the Secret Service: The Spy on Two Fronts (London: Hutchinson, 1930); H.C. Bywater and H.C. Ferraby, Strange Intelligence: Memoirs of Naval Secret Service (London: Constable & Co., 1931, rep. Biteback Publishing, 2015); J. Kearful, “A Radio Technician Made History,” Field Artillery Journal, 50 (1950), May-June, pp. 128-29; H. Landau, The Spy Net: The Greatest Intelligence Operations of the First World War (London: Jarrolds, 1938, rep. Biteback Publishing, 2015); J. Maclaren and N. Hiley, “Nearer the Truth: The Search for Alexander Szek,” Intelligence and National Security, 4 (1989), 4, pp. 813-26; M. Occleshaw, Armour Against Fate: British Military Intelligence in the First World War (London: Columbus Books, 1989); S. Roskill, Admiral of the Fleet Earl Beatty: The Last Naval Hero (London, 1980).

Fascinating! Another example of how storytelling will never die. People love a good story, even at the cost of fact.

So right about revisionist backstories. I’ve seen my fair share!