Spying is an activity that naturally attracts more than its fair share of charlatans, but the case of John Honeyman is intriguing because, while he’s long enjoyed a storied reputation as one of the great operatives of the American Revolution, he himself is innocent of any charlatanry.

It was other people who claimed he was a spy, in other words. And still do, come to think of it.

So what’s he’s supposed to have done? Well, according to CIA’s own official history, “The Founding Fathers of American Intelligence,” if it weren’t for John Honeyman, General George Washington would have lost the key battle of Trenton in the dreadful winter of 1776-77.

At a time when Washington had suffered an agonizing succession of defeats at the hands of the British, it was Honeyman the Spy who brought the beleaguered commander precise details of the enemy’s weak dispositions at Trenton, New Jersey.

Soon afterwards, acting as a double agent, Honeyman misleadingly informed the Hessian commander that the Continental Army was on its last legs. That bitingly cold Christmas, nevertheless, Washington enterprisingly crossed the Delaware River and smashed the unprepared, apparently drunk Hessians.

Then, three days into the new year, he struck again, at Princeton, inflicting a stunning defeat, both tactical and strategic, upon the redcoats and inspiring new resolve within the Continental Army.

Stirring stuff, certainly, but Honeyman had nothing to do with any of it. All his daring exploits in the secret world were invented, or plagiarized—as we’ll see— many decades after these events.

Indeed, upon closer examination, the entire story is ridiculous from the get-go, yet it has nevertheless entranced historians for more than a century. But where did the story come from and what was its purpose? I’ll answer those questions in due course, but first, who was John Honeyman?

Background

Honeyman came from obscure origins, but was most likely born, of Scottish ancestry, in Ireland in 1729. He joined the Army and served under General James Wolfe at the battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759, the British victory eventually leading to the creation of Canada. Afterwards, he left the Army and in 1776 was in Griggstown, New Jersey, with his wife Mary and seven children, where he earned a living as a cattle-dealer, weaver, and farmer.

The story goes that in early November of year, as Washington’s battered forces retreated into Pennsylvania, Honeyman arranged a private meeting with the general at Fort Lee, New Jersey using a laudatory letter from Wolfe and his attachment to independence as his entrée.

It was then, in the words of the chief 19th-century source (the basis for all since), the two men decided that Honeyman was to serve as Washington’s spy while playing “the part of a Tory [Crown Loyalist] and quietly talk[ing] in favor of the British side of the question.”

His mission, once the Americans had left, was to collaborate with the enemy by selling the royal army cattle and horses and supplying the king’s soldiers with beef and mutton. He was to gain their trust and stay behind enemy lines, in other words, in order to observe British movements, fortifications, and logistics, plus gain advance knowledge of the enemy’s designs.

Now, such a meeting could have taken place. If you check Washington’s itinerary at the time, he was in Fort Lee, about fifty miles from Griggstown, for several days in mid-November. That such a senior officer would have a meet-and-greet with a former enlisted man is also very possible, for the 18th-century world was a smaller and more intimate one than our own. Washington might well have set aside a few minutes for a veteran and suggested that he glean what intelligence he could and transmit it to him.

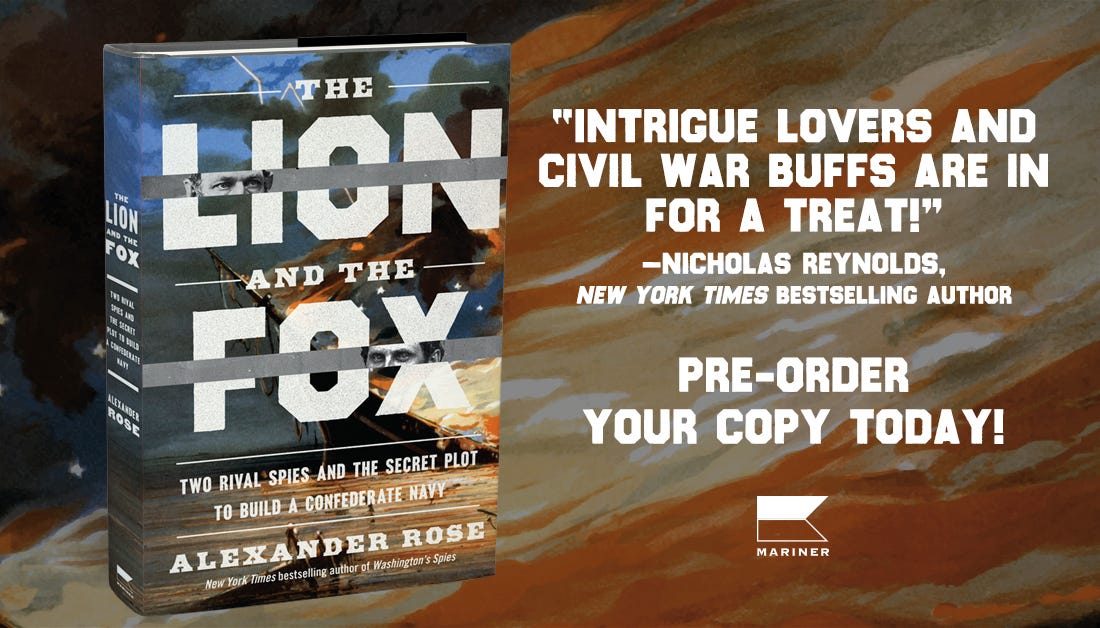

But against all this there’s not a single mention of Honeyman in any of Washington’s voluminous correspondence and papers. The general, as you’ll find in my book Washington’s Spies—had a very efficient secretarial staff who kept compendious records, including all his dealings with spies (such as the Culper Ring). Why is Honeyman missing, then?

Even granting that it was a Super Top Secret meeting that was kept off the books, the story still doesn’t ring true that Honeyman was recruited as a spy.

In fact, given the parlous state of the Continental Army at the time, Washington would have been far more eager to hire one of Wolfe’s boys, who at least knew their business, as a sergeant than a spy.

A Plan Out Of Time

More seriously, the historicity of the plan for Honeyman to remain permanently behind enemy lines in plain clothes is an anachronism that unwittingly demonstrates the falsity of any claim to his importance in late 1776. The fact is, Washington could call on only the most rudimentary intelligence apparatus at that stage in the War.

To maintain a civilian spy permanently in a hostile area bounded by armed pickets requires an advanced system of secure intelligence transmission, forged documents, trusted payments, and a network of couriers, among other things. Washington had none of that.

The general at that time accordingly used only soldiers (like Nathan Hale) in mufti to sneak behind enemy lines for a day or two, sniff around a bit, and come home. In short, there were no long-term agents masquerading as sympathizers with realistic cover stories operating anywhere in British-held territory.

It was a concept whose time had not yet come, and there is no way that Honeyman could have arranged to undertake such service. (It wouldn’t be until September 1778 that Washington began considering replacing reconnaissance with real spying—hence the importance of the Culper Ring.)

More Holes In The Story

Then there’s the matter of Honeyman’s exfiltration—how to get himself back into Washington’s camp after his undercover mission without raising suspicion among the British that he was a Yankee agent. According to the story, he and Washington cooked up the plan, which was: Honeyman the Tory Sympathizer would pretend to be out looking for some lost cattle near the border when two American scouts would spot him. After a prolonged pursuit to preserve his cover story, they would capture him when he slipped on some ice while scaling a wall. Even with two pistols pointed at his head, he would violently resist his subduers as they brought him to Washington’s camp.

It worked a treat. Upon arrival, Honeyman continued his masquerade by theatrically trembling and casting his eyes downward in shame. Washington instructed his aides and guards to leave and held a private debriefing with Honeyman before ordering the spy to be locked in the prison until morning, when he would be hanged following a court-martial.

By a remarkable coincidence, a fire erupted in the camp that night and Honeyman’s guards left to help put it out. When they returned, Honeyman had made good his escape and returned to the British side, his cover intact. The fire, according to this account, had been set on Washington’s orders, and the general feigned extreme anger that the “traitor” had evaded his doom.

Honeyman then went to see the Hessian commander Colonel Rall, who quizzed him about the whereabouts and strength of the Americans. The double agent accordingly spun a tale about Washington’s army being too demoralized and broken to mount an attack, after which Rall fatally exclaimed that “no danger was to be apprehended from that quarter for some time to come.” And so the die was cast.

Honeyman, knowing his ruse could not last long once Washington crossed the Delaware to launch his surprise attack, and understanding that “there was little if any opportunity for the spy to perform his part of the great drama any further,” thereupon vanished until the end of the war.

The Letter

A good thing, too, for the story continues that news of Honeyman’s escape from Washington’s camp enraged his family’s Patriot neighbors in Griggstown. For some time, says the primary source account, he’d been known as “Tory John Honeyman,” but now he was accused of being a “British spy, traitor and cutthroat.”

Consequently, an indignant, howling mob surrounded his house at midnight, terrifying his wife and children. Mary eventually invited a former family friend (now the crowd’s ringleader) to read out a piece of parchment she had hitherto kept safely hidden.

Upon it was printed:

To the good people of New Jersey, and all others whom it may concern,

It is hereby ordered that the wife and children of John Honeyman, of Griggstown, the notorious Tory, now within the British lines, and probably acting the part of a spy, shall be and hereby are protected from all harm and annoyance from every quarter, until further orders. But this furnishes no protection to Honeyman himself.

Geo. Washington

Com.-in-Chief

Whereupon the crowd grew silent and dispersed. His family was henceforth left alone, but Honeyman could never come home.

Tory John Honeyman

Look, come on, this is clearly a ridiculous story, at once inordinately complex and childishly simple. There’s a lot more I could delve into at this point—and have, in an article I wrote a long time ago for the CIA journal, Studies in Intelligence—but let’s cut to the chase.

A rather probable explanation for Honeyman’s being known as “Tory John Honeyman” and his desperate attempt to avoid falling American hands and the threat of a court-martial was that he actually was a Tory. Hundreds of Loyalists were being rounded up at the time; sometimes they were hanged as spies.

Perhaps Honeyman had wandered too close to the line and got picked up on suspicion of reconnoitering the American pickets, or he was grabbed when some of his neighbors pointed him out as a known troublemaker. Who knows? The point is that he was given a scare, a warning, and kicked out of the camp.

As for his later convincing an officer as shrewd and as experienced as Rall with his cockamamie tale of escaping the hangman’s noose, I think we can safely say that no such meeting occurred.

And last, Honeyman did not, in fact, vanish for the rest of the War—as local court records attest (but his advocates forget to mention). For instance, on July 10, 1777— more than six months after his “disappearance”—he was the subject of an American proceeding to seize his property “as a disaffected man to the state” of New Jersey. In early December, he was actually jailed and charged with high treason by the state’s Council of Safety, but he was eventually released after pledging a bond of £300 to refrain from Loyalist/Tory activity.

Then, on June 9, 1778, he was indicted for giving aid and succor to the enemy between October 5, 1776 (about two months before he allegedly volunteered to serve Washington) and June 1777. The authorities threatened to confiscate his house and property but relented, probably because Honeyman had kept his nose clean since paying the £300 bond for good behavior.

What we have here, then, is a low-level Tory who remained one, though fairly quiescent after his brushes with the Patriot authorities. He was nobody special; there were thousands just like him trying to walk a delicate line during a hard war.

So how on earth did John Honeyman become one of America’s greatest spies?

The Creation Myth

Every myth has an origin, and in Honeyman’s case that origin was an article in a New Jersey monthly magazine called Our Home. Appearing in 1873, almost a century after the events it breathlessly related and some fifty years after Honeyman’s death (in 1822, aged 93), it was written by his grandson Judge John Van Dyke (1807–78).

“An Unwritten Account of a Spy of Washington” first fleshed out the Honeyman legend in all its colorful and memorable detail. Van Dyke’s revelations made a significant stir, not just because it weaved a fine story, but because of the timing of its appearance.

The newly reunited nation was preparing for the centenary celebrations of the Declaration of Independence. Having but recently emerged from the bloodiest of civil wars, Americans were casting their minds back to those worthy days when citizens from north and south rallied together to fight a common enemy.

Honeyman was thus upheld as a gleamingly patriotic exemplar to Unionists and Confederates alike. When organizations like the Sons of the American Revolution and the Daughters of the American Revolution were founded in 1889 and 1890 respectively, they accordingly exalted Honeyman as representing the unity and purpose of the Founding Fathers.

In 1898, Honeyman was prominently featured in a popular book of the time, William Stryker’s Battles of Trenton and Princeton, and from there his fame only grew as the savior of Washington in those dark days. By the 1950s, Honeyman was the star of an article in American Heritage magazine that cemented his reputation as the ace of spies, then later in several bestselling books.

He continues to pop up, not least in a recent “documentary” on the American Heroes Channel and popular histories of American intelligence.

Indeed, in July of this year, he was the subject of an admiring and amusingly terrible/gullible “documentary” (sorry for the repeated scare-quotes, but they’re apposite in these cases) on the Fox Nation streaming channel: “John Honeyman—The Secret Weapon.” It was part of a series called Untold: Patriots Revealed, which informed viewers that “his heroics stayed a secret, until now.”

Perhaps they should have stayed that way, for the episode broadcast centuries-old fake news about a quintessential American hero who was, in fact, a man of modest accomplishments and uncertain loyalties.

The Real Secret Revealed

The most important thing to know if we want to solve the Honeyman mystery is that Judge Van Dyke colorized but did not invent the story in his Our Home article.

In a letter dated January 6, 1874, the judge revealed that he had originally heard the tale from the “one person who was an eye and ear witness to all the occurrences described at Griggstown”: his Aunt Jane, Honeyman’s eldest daughter, who had been 10 or 11 in the winter of 1776/77.

Jane had been present when the Patriot mob surrounded the house after Honeyman’s alleged escape and, in the words of Van Dyke:

She had often heard the term ‘Tory’ applied to her father. She knew he was accused of trading, in some way, with the British; that he was often away from home most of the time; and she knew that their neighbors were greatly excited and angry about it; but she knew also that her mother had the protection of Washington. She had often seen, and read, and heard read, Washington’s order of protection, and knew it by heart, and repeated it over to me, in substance, I think, in nearly the exact words in which it is found in the written article [Alex: the letter from Washington reproduced above].

Now we’re getting somewhere. Aunt Jane, it seems, was the sole source for Honeyman’s exploits. As she died in 1836, aged 70, Van Dyke must have elicited the details from her some forty years earlier and so had plenty of time to mix lashings of make-believe into Aunt Jane’s original tale, itself stitched together from her adolescent memories of events that had occurred six decades previ- ously.

We know a little about Jane. She stayed at home, being the only child of Honeyman never to have married. According to a contemporary description, “she was a tall, stately woman, large in frame and badly club-footed in both feet. She was a dressmaker, but had grace of manners and intelligence beyond her other sisters.”

Would it be any wonder if clever, imaginative Jane—doomed to long spinsterhood by her appearance, and fated to look after her aged and ailing father for decade after endless decade—had embroidered a heroic tale to explain what had really happened?

But how had she come to invent the story of a man involved in valiant deeds of spying for Washington while stoically suffering the abuse of his neighbors, family, and ex-friends?

The Spy

The answer lies in the dates. John Honeyman died, as I mentioned earlier, in the summer of 1822. One year before, the up-and-coming novelist James Fenimore Cooper (1789–1851), future author of The Last of the Mohicans, had published what is today counted as the first American espionage novel, The Spy: A Tale of the Neutral Ground.

In this Walter Scott-like historical romance, Washington played a cameo role while the hero was Harvey Birch, an honest peddler who refuses to accept money for his undercover work for the American side during the Revolution. Owing to a series of melodramatically crossed wires, Birch finds himself accused of treachery and is pursued by British and Americans both.

Only Washington knows the truth of the matter but is obliged to remain silent to maintain Birch’s cover. At the end of the war, Washington confides to the faithful Birch during a secret meeting that “there are many motives which might govern me, that to you are unknown. Our situations are different; I am known as the leader of armies—but you must descend into the grave with the reputation of a foe to your native land. Remember that the veil which conceals your true character cannot be raised in years—perhaps never.”

Then, Washington wrote “a few lines on a piece of paper” and handed it to Birch. “It must be dreadful to a mind like yours to descend into the grave, branded as a foe to liberty; but you already know the lives that would be sacrificed, should your real character be revealed,” the great man cautions. “It is impossible to do you justice now, but I fearlessly entrust you with this certificate; should we never meet again, it may be serviceable to your children.”

Then the action fast-forwards to the War of 1812. Near its end, we find Birch, who has lain low in the ensuing decades owing to his seemingly opprobrious conduct, again secretly struggling for the cause of liberty, again against the British.

Two young American officers catch sight of him, wondering who this odd, old, solitary, ragged figure is, but the sound of approaching fire delays hurries them away. Following the battle, they discover that Birch mounted a brave solo effort to capture prisoners but never returned.

They find his corpse, at peace. “He was lying on his back [and] his eyes were closed, as if in slumber.” Birch’s “hands were pressed upon his breast, and one of them contained a substance that glittered like silver.” It was a tin box, “through which the fatal lead had gone; and the dying moments of the old man must have passed in drawing it from his bosom.” Opening it, the officers found a message from many years before:

Circumstances of political importance, which involve the lives and fortunes of many, have hitherto kept secret what this paper now reveals. Harvey Birch has for years been a faithful and unrequited servant of his country. Though man may not, may God reward for his conduct!

—GEO. WASHINGTON

After this bombshell, Cooper resoundingly concludes that the spy “died as he had lived, devoted to his country, and a martyr to her liberties.”

Splendid stuff, the sort of thing that turned The Spy into an enormous hit and assured Cooper’s status as the preeminent American novelist of the era.

With that in mind, it wouldn't be outlandish to suppose that Aunt Jane read it around the time her father died. Could she, in order to consecrate her father’s silent martyrdom and to hush those neighbors still gossiping about his dodgy wartime past, have merely plagiarized Cooper’s basic plot and final twist?

Yet the Honeyman story’s myriad anachronisms and suspiciously detailed narrative signal the skilled warp and weft of Judge Van Dyke’s handiwork. Even its tone mirrors the kind of High Victorian sentimentality and romanticism that washed over Civil War and Reconstruction-era espionage writing and memoirs. All those beautiful belles and lantern-jawed heroes saving their nations from peril in the most fanciful way . . . How could Van Dyke not have hankered for his own Revolutionary forebear?

So it was Van Dyke who broadened the story’s focus, thrust, and intent far beyond what Aunt Jane had ever envisaged in her understandable desire to valorize her father. Between them, Jane and the judge endowed a most ordinary man with an extraordinary—and almost wholly fake—biography that continues to beguile the naive.

It was John Honeyman himself, curiously enough, who was innocent of telling tall tales. For more than half a century, he remained resolutely silent about his wartime behavior (as well he might, given his not altogether sterling record.)

Van Dyke, who “was with him very often during the last fifteen years of his life, and saw his eyes closed in death,” heard nothing of his grandfather’s past in all that time. His life was a blank slate upon which anything could be written. And so when Aunt Jane handed her nephew the ball, he ran with it.

It’s high time to let John Honeyman repose in peace.

Further Reading: A. Rose, “The Strange Case of John Honeyman and Revolutionary War Espionage,” Studies in Intelligence, 52 (2008), 2, pp. 27-41. This is a significantly more detailed examination of the Honeyman case. There are many instances of Romantic Honeymanism, aside from those mentioned in this post. See, for example, R.M. Ketchum, The Winter Soldiers (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1973); J. Bakeless, Turncoats, Traitors, and Heroes: Espionage in the American Revolution (NewYork: Da Capo Press, 1998 edn., orig. pub. 1959). For the original sources, Minutes of the Council of Safety of the State of New Jersey (Jersey City, NJ: John H. Lyon, 1872); J. Van Dyke, “An Unwritten Account of a Spy for Washington,” Our Home, 1873, reprinted in New Jersey History, LXXXV (1967), Nos. 3 and 4; W.S. Stryker, The Battles of Trenton and Princeton (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1898); A. Van Doren Honeyman, The Honeyman Family (Honeyman, Honyman, Hunneman, etc.) in Scotland and America, 1548–1908 (Plainfield, NJ: Honeyman’s Publishing House, 1909). For those interested in Victorian spy melodrama, see R.B. Marcy, “Detective Pinkerton,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, XLVII (1873), 281, pp. 720–27; L.C. Baker’s heavily fictional memoir, History of the United States Secret Service (Philadelphia: L.C. Baker, 1867); R. O’Neal Greenhow, My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington (London, UK: R.Bentley, 1863); B. Boyd, Belle Boyd in Camp and Prison, Written by Herself (New York: Blelock, 1865). Most of their content is exaggerated at best, invented at worst.