An old CIA saw is that spies work for at least one of the following reasons: Money, Ideology, Coercion, Ego.

Now, sometimes Coercion is switched to Compromise—the genteel word for blackmail—or Conscience, and I’ve seen cases where Ego is replaced by Excitement, but the MICE principle nevertheless remains a useful taxonomical method of categorizing the various genera and species of spies.

The British traitor Kim Philby, for instance, served the KGB for ideological and egotistical reasons, whereas the American turncoat Aldrich Ames may have wanted, like the too-clever-by-half Philby, to get one over his over-promoted colleagues but primarily he worked for cash.

The picture muddies, however, when we’re dealing with pre-modern spies whose motivations are opaque, the culture very different, and where we have only fragmentary documentary evidence to hand.

The most interesting case I’ve come across is that of the 16th-century Italian Jewish agent, Simon Sacerdoti, who worked for, of all people, the Habsburg king Philip II (1527-1598), who refused to allow Jews in Spain, let alone into his presence— yet made a unique exception for him.

Jews and the Mediterranean World

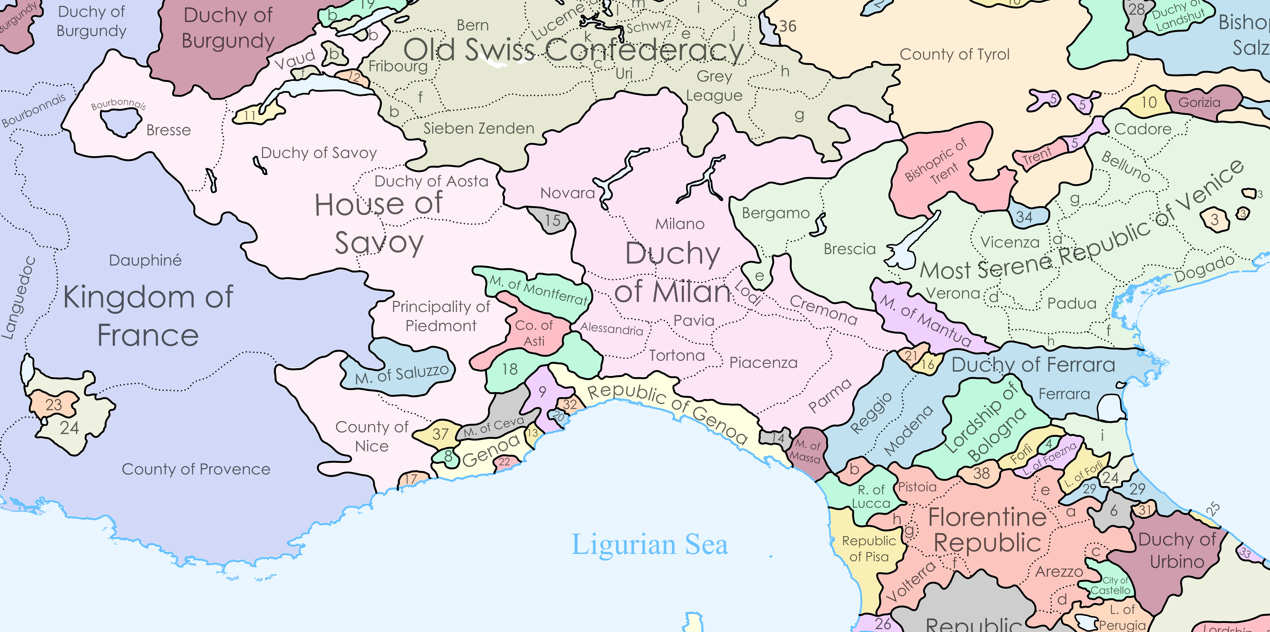

Jews occupied a precarious position in the Mediterranean, which in Sacerdoti’s day was more or less divided into Spanish and Ottoman spheres of interest, with important cameos played by the Italian city-states like Venice or Genoa and France occasionally joining in to annoy Philip. (The English preferred the Atlantic, where they contented themselves hijacking his galleons, groaning under the weight of all that New World gold.)

It was a tightly interwoven, cross-cultural environment where traders, corsairs, princes, mercenaries, clerics, and scholars traversed Homer’s wine-dark sea to an extent perhaps surprising to those who believe our own globalized world has had no equal.

Neither Christian fish nor Muslim fowl, Jews—some native to the Levant, and others expelled from Spain by the Inquisition—were regarded as important middlemen between the west and the east. They could blend in and adapt to either culture, and served to explain the manners and customs of the sultan’s court to Italians, Portuguese, and Spaniards and vice versa.

As a form of self-protection from the vagaries of any one sovereign’s whim—expulsions, massacres, exhorbitant fines, and the like—the great Jewish trading families established far-flung branches around the Mediterranean and within Europe, each part of a self-supporting network.

As such, family members were often employed as spies, information-gatherers, and confidential couriers while carrying out their everyday business. David Passi, for instance, a Jewish spy (and double agent) of Spanish origin who lived in Dubrovnik and worked for the Venetians, had a wife in Ferrara, a brother at the royal court of Poland, a father in Salonica, and an uncle in Constantinople.

The Information Trade

The Sacerdotis were of a piece. After the Expulsion of 1492, they settled in Alessandria, a town in the Duchy of Milan, where the family patriarch founded a bank and went into the wheat trade. They were the first Jews to arrive. A grandson, Simon, was born circa 1530. In 1556, Alessandria fell under Spanish Habsburg rule and the small but growing Jewish population lived under constant threat of an expulsion.

Hoping to make himself invaluable to his new overlords, young Simon entered the secret world in 1560, when he embarked on the first of at least ten clandestine missions on behalf of Philip II. In the beginning, he worked for the royal governor, stayed fairly local (Zurich and Germany), and worked cheap (between eight and twenty silver scudi, the Milanese currency), but by 1568 he’d been upgraded by Madrid and was being paid no less than 150 gold scudi for a commissione secreta. These later missions seem to have taken him to Jerusalem and Constantinople.

King of the World

Formally known by the title of Rex Catholicissimus—Most Catholic Majesty—Philip II was familiarly known as El Rey Papelero—the Paperwork King—owing to his obsessive-compulsive micro-managing of his vast dominions that sprawled from the Americas to the Philippines. Whereas his predecessor Emperor Charles V ruled the world by means of nods, Philip’s busyness once generated a 49,555-page report on Peru that required thirteen years to complete.

Accordingly, unlike Elizabeth I, who outsourced her intelligence system to Sir Francis Walsingham, or the Venetians, whose secretive Consiglio dei Diece (Council of Ten) managed the most sophisticated intelligence-gathering agency and assassination bureau in the world, Philip personally read every ciphered report from his ambassadors and governors. In short, owing to their many letters extolling Sacerdoti’s talents, he was long aware of the services this Jew was providing.

Simon also cultivated several high-level allies among Philip’s confidantes, buying further protection for him and his family’s position in Milan. Among them was an Aragonese nobleman named Don Martin de la Nuca, a close friend of Antonio Pérez, the king’s secretary—an interesting fellow we’ve met before here at Secret Worlds (see below, “The Magnifico”)—and Emmanuel Philibert, the Duke of Savoy and Philip’s cousin.

The Buggia Plan

Judging by his actions in Buggia, a formerly Spanish fortified city on the North African coast that he had been captured by the Ottomans in 1555, Sacerdoti had added the role of covert operative to that of spy.

In 1569-70, he proposed an audacious plan to Savoy to retake Buggia. The Duke in turn reported to Philip that Sacerdoti had a friend in nearby Argel named Geronymo Nicardo, a sailor, who had told him that the Turks had slipped up and left Buggia with a garrison of only fifty elderly Janissaries.

Accompanied by a handful of accomplices, Sacerdoti intended to visit the city to present its caliph with lavish gifts. Once in the palace, the caliph would be killed and then a larger force of 150-200 men hidden offshore in merchant ships would be signaled while his team took care of a few guards and unlocked the gate, Trojan Horse-style.

In case the ships were stopped and searched by the Ottomans on the way there from Marseille, the expeditionary force’s weapons would be hidden in sealed compartments within wine barrels. (This method was used by seditious English Protestants to smuggle their heretical tracts into Spain, Sacerdoti revealed to an astonished Philip.)

The king favored the scheme, only for it to come undone in September 1571 when Sacerdoti was captured by the Marseille authorities and confessed all. Even so, the Duke of Savoy was still keen to press forward but the Battle of Lepanto on October 7 put it on the backburner.

That glorious victory over the Ottoman fleet by a Spanish-Venetian alliance made Buggia a lesser priority as Philip struggled to keep the squabbling coalition together to exploit the Turks’ travails.

For the next couple of years, Sacerdoti lay low, but in 1574 he again raised the Buggia plan. He had a source who was privy to the correspondence between the King of France and his secretary—Sacerdoti had fingers in many pies—and they’d been discussing storming Buggia and taking it for themselves while Philip wasn’t watching. Sacerdoti suggested swiping it before the French did.

This time, though, Philip was more cautious. He now considered Sacerdoti “to be a man of [not] much standing or seriousness and it is understood that very little will come out of this.”

Buggia was dead.

The Privilege of Savoy

Philip’s newfound scepticism had been prompted partly by his displeasure that Sacerdoti had blown the plan to the French in 1571, but mostly because of his activities in 1572-73, when he’d left Spanish secret service.

During that interval, Sacerdoti had been back in Italy advising the Duke of Savoy on Jewish affairs. Emmanuel Philibert was rare in having had good relations with selected Jews, though he perhaps shouldn’t be counted as some modern progressive: The Duke had earlier twice expelled the Jewish community from his lands, only to relent upon receiving a sizeable tribute.

Now it was different. On September 4, 1572, he opened his territory to Jews driven out of the Papal States and granted trading and banking privileges to all Jews, including the conversos (Spanish and Portuguese Jews purportedly converted to Christianity) fleeing his cousin’s Inquisitors. More remarkably, Constantinople’s Jewish merchants were invited to open branches in his duchy, which he envisaged as a kind of free-trading clearing-house where, as he said, “Turks, Armenians, Persians, Indians, and Levantines” would be granted safe-conduct in his ports and cities.

Much of this extraordinary development was owed to Simon Sacerdoti.

The experiment didn’t last long. Philip went nuts when he heard about the duke’s presumption. Spanish forces in Italy were put on alert and Philip drew the Pope’s attention to this outrage. In May 1573, under extreme pressure and threatened by excommunication, Emmanuel Philibert ended the Privilege and expelled the Jews from Savoy.

Sacerdoti’s Later Years

In light of Sacerdoti’s influence on the wayward Emmanuel Philibert, we can understand Philip’s relegating him to the doghouse in 1574. Still, Sacerdoti was too useful to stay there forever. Two years later, he embarked on a mission for the Spanish governor of Milan, and again in 1580 and 1584. By 1591, now aged about 60, Sacerdoti had retired from the secret world but now came in from the cold to perform one last task.

That year, after decades of hemming-and-hawing, Philip had at last decided to expel the Jews of Milan, but in recognition of his services to Spain, Sacerdoti was granted the honor of a safe-conduct guarantee to come to the imperial court for an audience with the king.

One source recorded that Simon took the opportunity to plead with Philip on behalf of the Milanese Jewish community, while another mentions that he was concerned with ensuring that his earlier debts undertaken in the king’s service were repaid. It was probably a bit of both.

What seems beyond doubt is that Sacerdoti was an extremely persuasive individual. He had worked wonders on the Duke of Savoy, and now he tried to do the same with the King of Spain. He succeeded, to a point: Philip agreed that it was only Christian to pay one’s debts, so that was a relief.

But the question of issuing another condotta—the contract that permitted Jews to stay—was another matter. Sacerdoti did his best by submitting a detailed memorandum deploying the theological, legal, and practical arguments for extending their privileges. For instance, that it offended Christian charity to expel guests and, in any case, how else could the Jews be expected to convert to the One True Faith—and here Sacerdoti mentioned two sisters and a brother who had “gone to Rome,” as they say—if they were forced to depart for heathenish lands?

No, didn’t work. Philip remained immoveable, though he graciously conceded that the Jews could stay until the Crown finished paying its accumulated debts to the community. After that, presumably, they could be despoiled on their way out the door.

Still, better than nothing. In the event, owing to the financial complexity of sorting out decades’ worth of interest and loans, as well as a lot of slow walking, it took until 1597 for Milan’s 900-strong Jewish community to be sent packing. Philip in the meantime had grown increasingly frail (and furious—that this Jewish thing was going on so long) and died a year later.

It would be the last Spanish expulsion of European Jews, but as for Simon Sacerdoti, Philip remembered his good and faithful servant. He and his family were the only Jews granted an exemption from the banishment and were, as a mark of royal esteem, allowed to continue residing in the city. They would be the only Jews in the entire state of Milan for the next two hundred years.

The Mystery of Sacerdoti

The question remains: Can we classify Sacerdoti according to the MICE principle?

I think we can remove Ideology from consideration, as Simon owed no natural allegiance to Spain and would happily have worked for the Ottomans in different circumstances. It would have made his life much simpler to convert, yet he didn’t.

Ego can’t be ruled out. Obviously, we know nothing of Sacerdoti’s character but his enthusiasm for mounting special ops would seem to indicate a man seeking excitement. He could easily, after all, have remained at home rather than risk his neck in foreign ventures.

As for Money, Sacerdoti, of a banking family owed significant debts by Madrid, no doubt kept a beady eye on being paid for his services. But that doesn’t strike me as the primary motivator in this case, for he doesn’t appear to have turned a profit. If anything, he lost money waiting for his costs and debts to be dealt with.

Which leaves Coercion, in the sense that Sacerdoti knew he and his fellow Jews lived under the constantly recalibrating threat of expulsion, expropriation, and exsanguination. They always had to tread carefully, balance interest against interest, keep options open, eye escape routes, and placate the powerful—in this case, Philip II, influential nobles, and royal administrators.

Sacerdoti acted consistently on the basis of postponing the evil day in the Micawberish hope that “something”—a friendly duke, a helpful governor—would turn up and save the Jews, at least temporarily. Whether he wanted to or not, Sacerdoti had to involve himself in the secret world to generate goodwill and forbearance.

That he discovered a taste for the dark arts provided, at least, a modicum of cold comfort.

Further Reading: F. Cassen, “The Last Spanish Expulsion in Europe: Milan, 1565-1597,” AJS Review, 38 (2014), 1, pp. 59-88; F. Cassen, “Philip II of Spain and His Italian Jewish Spy,” Journal of Early Modern History, 21 (2017), 4, pp. 318-42; E.S. Gürkan, “Dishonorable Ambassadors?: Spies and Secret Diplomacy in Ottoman Istanbul,” Archivum Ottomanicum, 35 (2018), pp. 47-61; I. Iordanou, “The Spy Chiefs of Renaissance Venice: Intelligence Leadership in the Early Modern World,” in P. Maddrell, C. Moran, I. Iordanou, and M. Stout (eds.), Spy Chiefs: Intelligence Leaders in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2018); N. Malcolm, Agents of Empire: Knights, Corsairs, Jesuits, and Spies in the Sixteenth-Century Mediterranean World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015); G. Parker, The Grand Strategy of Philip II (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1998).