Failure to Communicate

A Civil War Secret Agent's Struggles with a Cipher

Note: I originally included parts of this newsletter in my forthcoming book, The Lion and the Fox, though I decided to cut the cipher sections to keep the story moving along. So, think of this as one of those “Extras” you used to get on DVDs.

In other news, my estimable publisher has just informed that it’s giving away 25 free copies of the book on GoodReads come December, so if you’d like to throw your hat into the ring, please click here.

Alrighty, moving on . . .

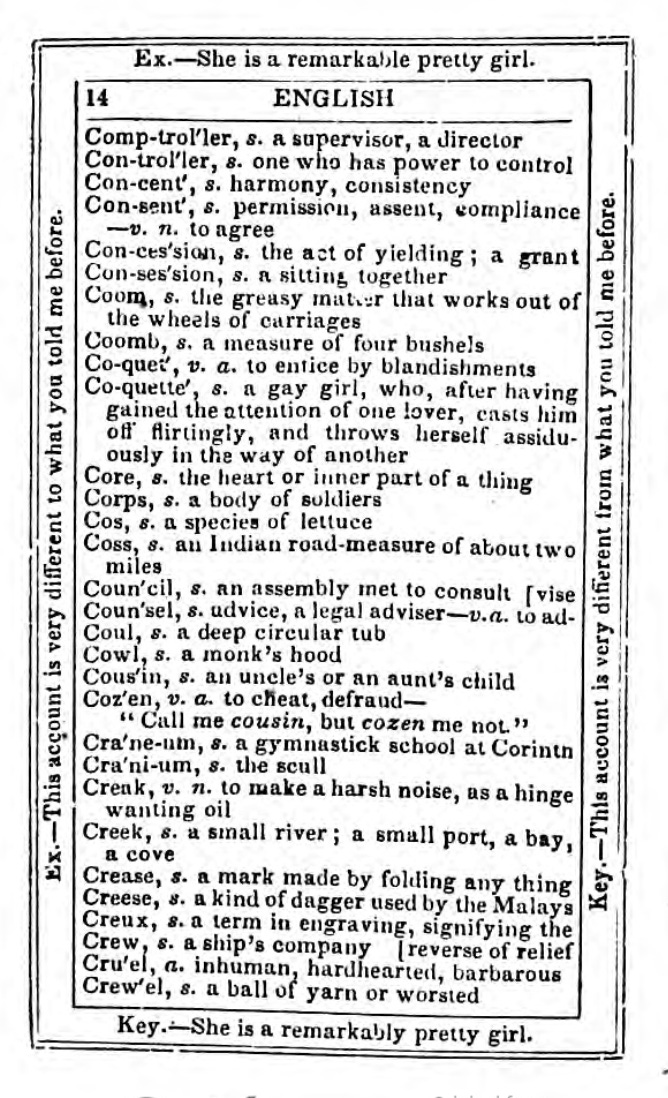

In May 1861, less than a month after the bombardment of Fort Sumter that opened the Civil War and shortly before he embarked on his secret mission to purchase a Confederate Navy in Britain, the Southern agent James Bulloch was told by the freshly installed Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory to buy the latest edition of Lyman Cobb’s Reticule and Pocket Companion; or, Miniature Lexicon of the English Language.

The two of them, explained Mallory, were to use a “dictionary code” to encrypt their correspondence. In their simplest form, dictionary codes use two numbers, separated by a period or parentheses, to represent a certain word. So, “ship” is represented by “674.26”—turn to page 674 in Cobb’s Miniature Lexicon and count down to the 26th word on that page. It’s a very quick and easy method, but not very secure.

I discuss dictionary codes in greater detail in Washington’s Spies, but to summarize:

First, they only work dependably if no one else but the sender and recipient knows the particular book being mutually used. Since any half-decent codebreaker who intercepted a message would always start by checking dictionaries—the go-to source owing to the ease of finding words—it would be only so long before Cobb’s Miniature Lexicon was consulted.

A second weakness is lack of randomness. A navy man communicating with the Secretary of the Navy about matters naval is very likely to have frequent recourse to a word like “ship.” Even without having the right dictionary at hand, cryptanalysts would search for giveaway patterns like the repeated use of “674.26” in predictable contexts to help crack the puzzle.

Partly explaining Mallory’s uncharacteristic carelessness with his communications was that the technical aspects of Civil War cryptography, especially in the fighting’s early stages, was rudimentary, so this was the best that could be done.

Keep in mind, too, that the encryption system had to be simple to operate in the field by untrained agents like Bulloch, who was rushing off on his mission the next morning. No doubt he stopped by an bookstore to pick up a copy of Cobb’s handily portable Miniature Lexicon before he left.

The Cipher

In the event, Bulloch rarely resorted to the dictionary code, trusting instead to the inviolacy of the British mail—interfering with it was a serious crime—and the ease of sending letters via the many blockade-runners leaving Liverpool and racing for Southern ports. When he wrote to Mallory he instead adopted, as he said, “a somewhat vague mode of expression” for the sake of security. By that Bulloch meant he used euphemisms and allusions for anything particularly sensitive, and never mentioned names or places.

In mid-1863, nevertheless, Bulloch briefly switched to a new cipher, much more secure, out of necessity. As a result, his typically flowery, ornately phrased language disappeared and his letters, now better described as “notes,” became clipped, choppy, and curt—sure signs of someone trying to relieve the tedious task of enciphering his own needlessly lengthy epistles.

The reason for the change was that Bulloch was then arranging a highly illegal deal with a corrupt shipbuilding firm and a dubious French arms merchant to build two of the world’s most advanced warships. His nemesis, Thomas Dudley, the United States consul in Liverpool, had lately scored too many intelligence successes and so Bulloch had an interest in keeping his activities very discreet.

The mystery is: Which cipher did Bulloch use? Well, unfortunately, he never said, but we have a couple of clues that can lead us to a suppositive answer.

It was almost certainly a Vigenère Cipher, originally developed by the French cryptographer Blaise de Vigenère (1523-1596), but which had come back into fashion around the time of the Civil War. It was often used by Confederate generals, senior politicians, and diplomats, and occasionally by conspirators with an understandable need for security—such as John Wilkes Booth, in whose hotel room a Vigenère would be found after Lincoln’s assassination.

Learning the Vigenère process wasn’t something one could simply pick up or guess at. It required either a dedicated secretarial staff or some one-on-one training by an expert, which is what happened in Bulloch’s case.

In March 1863, Secretary Mallory had sent Lieutenant William Murdaugh to Britain to teach Bulloch the cipher’s arcane secrets. Murgaugh was in the Confederate Navy but was attached to the Ordnance Department. At the time (I talked about this in American Rifle), Ordnance, for both the North and South, was home to the military’s brainboxes: If you were a mathematician or a physicist, you went to the 19th-century version of DARPA. Hence the fact that Murdaugh understood the Vigenère and was seconded to Bulloch gives some indication of how seriously ciphering was being taken.

How the Cipher Works

The Vigenère is a related, but very different, beast to the ancient Caesar Cipher, a monoalphabetic substitution system once employed by the great Julius to prevent his correspondence from being read by semi-literate barbarians and today used by 10-year-olds to write “secret messages” to each other to annoy their parents.

In it, the codemaker simply replaces a plaintext letter with one located in a fixed position behind or ahead in the alphabet. Thus, with a one-letter shift to the right, DOG becomes EPH, and to the left, CNF. Caesar preferred a three-letter shift, so A would become D, and DOG would convert to GRJ. For obvious reasons, once one works out the shift, his eponymous cipher takes just a few seconds to break.

The Vigenère, in contrast, was a polyalphabetic substitution cipher. It used a 26x26 square (the tabula recta) with the A-Z alphabet running across the top and then on subsequent rows shifted one letter, so the next line after A would start with B and the third, C, and so on all the way to Z, allowing up to 26 different alphabets.

The Vigenère relied on a key—a phrase or word—known only to sender and recipient. The writer would compose his message using this repeated phrase/word, switching alphabets each time for subsequent letters in the key. (The reader would reverse the process.)

An advantage of the Vigenère over the Caesar and other substitution ciphers is that it reduced the risk of frequency analysis, otherwise known as “counting letters,” a decryption method widely known among experts in the nineteenth century but which smelled of occult knowledge among a then-naive public. Edgar Allen Poe made it famous in his 1843 short story, “The Gold-Bug,” in which treasure-hunters decipher a cryptogram describing the location of the pirate Captain Kidd’s lost trove.

Frequency analysis simply consists of understanding that certain letters, combinations, or repetitions of letters appear more frequently than others. Any Scrabble player knows that E, T, A, and O are the most common letters, while the bigrams TH and ER appear all the time, and the repetitions SS or EE are often seen. The letters X, J, Q, and Z, on the other hand, are troublesome, because they appear the least.

Cracking a good Vigenère by hand is enormously difficult because, unlike a Caesar, where E is always F and EE always FF, it uses multiple alphabets shifting constantly based on the secret key (E can initially be a D, then switch to become a T, then change to H, and so on). Even the usual giveaway repetitions like EE will have two different letters standing for them (JV, for instance, and then YK).

Nevertheless, it was possible to do it, but only if you were a genius. In 1854, the English mathematician and computing pioneer Charles Babbage had broken a Vigenère for a challenge set by the Royal Society of Arts (the enciphered text was from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Act 1, Scene 2), but because it had military application his method remained confidential.

Then in 1863, the same year as Bulloch adopted it, Friedrich Kasiski, a retired Prussian Army officer, published a short book on cryptography that described the process by which one could attack the Vigenère. His method was almost certainly the same as Babbage’s.

The Kasiski Examination, as it was called, focused on hunting-and-pecking to find repetitions in a ciphered string (e.g., like CVXJ in HKDECVXJTUDWCVXJQPOZ). That would allow one to deduce the likely length of the key phrase/word, especially if the codemaker had sloppily used a too-short one to make life easier for himself.

Once you knew the length you could compile a table whose columns corresponded with the length of the key and with some elbow grease and midnight-candleburning turn it into a Caesar-style monoalphabetic substitution cipher, easily broken.

This was esoteric stuff, of course, and Bulloch appears to have made the task harder still by likely using a lengthy key of CATESBYAPRJONES (15 letters), a reference to the Welsh-named Catesby ap Roger Jones (“ap” means “son of”), the commander of CSS Virginia, the ironclad that had engaged the Monitor at Hampton Roads in March 1862 and accordingly one of his heroes.

Being an amateur, Bulloch would certainly have made a few mistakes, such as using a guessable key (Jones was a well-known figure), using a brass cipher disk as an aid (to allow faster but less secure encryption),1 retaining the same word length between plaintext and ciphertext (so a five-letter word remains five letters long), or omitting to encipher certain common words (thereby allowing one to guess context). Nevertheless, the system would have been more than sufficient to flummox Dudley, had he intercepted his messages.

The Courier

None of this really mattered, because the Vigenère was too onerous to use and Bulloch was becoming increasingly worried that Union capabilities were improving. He soon gave up using it in favor of a more traditional method.

Lieutenant William Whittle, aged 23, was for a time attached to him as a private messenger for his lengthier and more detailed letters. He would shuttle back and forth across the Atlantic carrying Bulloch’s correspondence with Mallory, and was under strict orders to destroy the documents if a Union vessel approached.

Using a courier was probably the most secure mode of intelligence transmission, but extremely time-consuming. Upon arrival in Liverpool, Whittle would first have to find Bulloch, give him Mallory’s letter, get Bulloch’s in return, book passage on a blockade-runner to Nassau, hitch a ride through the blockade, and finally travel to Richmond. And then do it all over again in reverse.

Given these difficulties, Bulloch was forced to operate mostly by his own wits for the rest of the War.

Further Reading: P. Bonovoglia, “Trithemius, Bellaso, Vigenère: Origins of the Polyalphabetic Ciphers,” in B. Megyesi (ed.), Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Historical Cryptology—HistoCrypt 2020 (Linköping University Press: Linköping, Sweden, 2020), pp. 46-51; J.F. Dooley, History of Cryptography and Cryptanalysis: Codes, Ciphers, and their Algorithms (Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018), pp. 68-71; D.W. Gaddy, “Secret Communications of a Confederate Naval Agent,” Manuscripts, 30 (1978), no. 1, pp. 49–55; Gaddy, “Internal Struggle: The Civil War,” in R.E. Weber, Masked Dispatches: Cryptograms and Cryptology in American History, 1775-1900 (Fort George F. Meade, Maryland: Center for Cryptologic History/National Security Agency, 3rd edn., 2013), pp. 88-103; P. Pesic, “Secrets, Symbols, and Systems: Parallels between Cryptanalysis and Algebra, 1580-1700,” Isis, 88 (1997), 4, pp. 678-80.

To make it easier, use this website.

https://hrefgo.com offers affordable AI APIs.

It also provides better cryptography tools: https://caesarcipher.org