When you’re the king of the world—an official title of the ancient kings of Assyria—you really need to watch your back. From your capital in Nineveh, nowadays in northern Iraq, you’ve got the Babylonians to the south, the Cimmerians to the west, the Elamites to the east, and the Urartuans to the north.

Sure, some of them are your vassals, but that never stopped them, often aided by the Egyptians, from trying their hand at an invasion when you’re not looking. Most Assyrian kings accordingly campaigned with their army every year or so to put out a fire somewhere in their vast empire, which encompassed today’s Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, half of Israel, south-eastern Turkey, and western Iran.

If the battles didn’t get you, then the court politics would. At home, you’re surrounded by potential enemies gazing at your throne with envious eyes. These range from your own sons to your uncles, from the hairless eunuchs to the bearded high priests, from the cupbearers to the seers. Any one of these men might be willing to kill you, given the chance.

A Family Affair

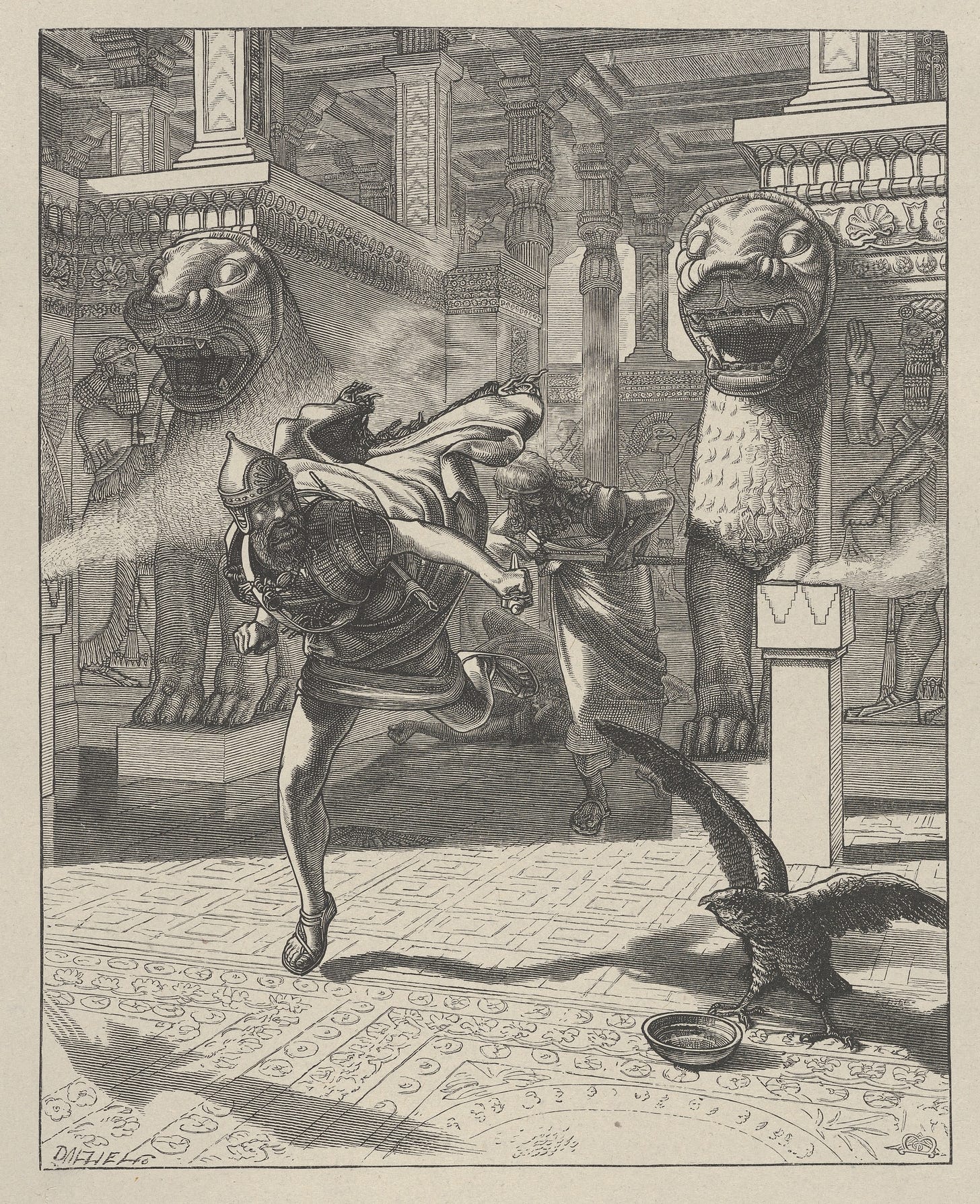

It happened pretty often, actually. Take Esarhaddon, the king (reigned 681-669 B.C.) who’s the subject of this issue. His grandfather Sargon II had seized the throne by murdering an usurper whose own father had come to power via a revolt. In turn, his (Esarhaddon’s) father, Sennacherib, had been murdered by two of his sons in a temple.

This profane act caused such a stir in the ancient Near East that it garnered a mention or two in the Old Testament (2 Kings 19:37; Isaiah 37:38):

“And it came to pass, as [Sennacherib] was worshipping in the house of Nisroch his god, that Adrammelech and Sharezer his sons smote him with the sword: and they escaped into the land of Armenia. And Esarhaddon his son reigned in his stead.”

What the Bible omitted to say was that the only reason why Esarhaddon was reigning at all was because Dad had earlier cut from the line of succession his eldest brother, one Arda-Mulissi, for various transgressions.

It was he, a bit of a bad ‘un, who was called “Adrammelech” by the chronicler, and it was he who induced his younger brother to join him. They both escaped and found asylum in Urartu—Assyrian enemies of long standing—where Arda-Mulissi was regarded as a useful tool to threaten Esarhaddon’s uneasy crown.1

It’s all enough to make you paranoid, which is exactly what Esarhaddon was, and sensibly so, because only the paranoid survive this kind of hostile work environment.

So, after executing all of Arda-Mulissi’s advisers, servants, and family just to be sure his brother had no informers in his household, Esarhaddon’s palaces were heavily guarded and made impregnable, he slept in a converted armory, and he trusted no man, only his female kin (his wife, mother, and daughter).

Locked away in his stone fastness, Esarhaddon understandably paid close attention to the reports of his spies about brewing intrigues. Much of it was hearsay, but one day he read something that shook him to the bones . . .

Assyrian Red Tape

We’re lucky to know so much about these time-dimmed events, the only reason being the extraordinary discovery and excavation of his son Ashurbanipal’s magnificent library in the mid-nineteenth-century.

Among other things, in the rubble the British Museum experts uncovered the Epic of Gilgamesh, forgotten for some two millennia but containing the first account of the Deluge—the basis for the Biblical story of Noah, the Ark, and the Flood.

Among the archaeologists’ other revelations was that the Assyrians enjoyed a remarkably advanced bureaucracy, staffed by a highly efficient cadre of scribes. They kept records in cuneiform of everything—diplomatic correspondence, taxation, government revenue, prophecies, the state of the armory—and it’s a general principle in the intelligence-history business that records are everything. The more files and folders, archives and catalogues a government has, the more effective its internal security and external-espionage systems tend to be.

The reason is that compendious records, if properly maintained and updated, allow both a centralized institutional memory to evolve (so that events can be contextualized and decisions made according to precedent, not individual whim) and for incoming information from one source to be cross-referenced against other sources in order to evaluate its validity.

In this case, we have relatively numerous records relating to the plot, though there’s necessarily some supposition.

An Extra-Spicy Extispicy

It all began with one Kudurru writing a worrying letter to Esarhaddon in 671.

A decade after assuming the throne, the king was in bad shape: Years of anxiety and distrust had resulted in relentlessly itchy skin rashes, spells of dizziness, an obsession with omens, and a fear of imminent violent death. He rarely emerged from his stronghold, ate little, and shunned company. He was getting older, too, and the thought of succession occupied his worried mind. As father to no fewer than eighteen children, there were plenty of heirs to choose from, or to fear.

In his letter, Kudurru, a diviner, exorcist, and refugee from Babylon who was under house arrest, informed the king that while he was confined, “Nabû-killanni the chief cupbearer sent [a cohort commander] to release me.”

After arriving at the temple of Bel Harran, Kudurru was taken upstairs, where Nabû-killanni, the court chamberlain, a general, and the “overseer of the city” were waiting. “They tossed me a seat and I sat down, drinking wine until the sun set,” whereupon they confirmed his expertise in divination.

He was then asked directly, “Will the chief eunuch take over the kingship?” (The chief eunuch’s name was Aššur-nasir.)

Kudurru “washed myself with water in another upper room, donned clean garments and, the cohort commander having brought up for me two skins of oil, performed [the divination] and told him: ‘He will take over the kingship.’”

Considerably cheered by the news, the plotters “libated a jug of wine . . . and made merry until the sun was low.” As reward, Kudurru was promised that he would return to Babylonia in triumph and become its king.

At that point, Kudurru explained to Esarhaddon why he had acted so. “The extispicy [which I performed was] but a colossal fraud! The only thing I was thinking of was, ‘May he not kill me.’” (For trivia-night fans, an extispicy is the practice of interpreting the entrails of sacrificed animals.)

He had told a lie to get himself out of a jam, but he was worried that Esarhaddon would “hear about it and kill me.” Hence the letter.2

Esarhaddon now had to decide what to do.

Enter Sasî

The most traditional and acceptable method of resolving this pickle would have been to kill everyone, immediately. But the men Kudurru had implicated had served Esarhaddon for many years, and executing them would leave him isolated in his own palace—and who would then protect him from plotters?

More to the point, Kudurru was hardly an unwitting participant. He’d already admitted he’d lied to save his skin, and he was the son of a rebellious, and now very dead, Babylonian chieftain. That was why he had been under house arrest in the first place (and promised the Babylonian throne). Conjuring up a conspiracy could very well have been a way of buying Esarhaddon’s trust before encouraging a Babylonian invasion.

As Esarhaddon noodled on the problem, a letter arrived, this time from a spy named Nabu-rehtu-usur warning of another plot. The details concern a slave-girl from nearby Harran, belonging to an official or magnate called Bel-ahu-usur, who ecstatically cried that the ancient Mesopotamian moon-god Nusku had proclaimed, “The kingship is for Sasî. I will destroy the name and seed of Sennacherib [Esarhaddon’s father].”3

This Sasî fellow was the city overseer, a kind of mayor-cum-governor, of Harran and the city at the time was regarded as home to a particularly accurate oracle, which meant this warning had to be taken seriously.

But was Sasî in league with the chief eunuch named by Kudurru, or were they part of separate conspiracies?

Judging by a follow-up letter, the former theory—that these were tip-offs exposing a grander plan—is probable.4 If I’m reading the records correctly, Kudurru had recently completed a magical course on “Evil Demons” under Sasî’s supervision, so it would make sense for the Eunuch Ring to use him as a cut-out for coordinating with the Sasî Gang.5

The Plots Thicken

Sasî’s identity is mysterious, but he was probably linked to the royal household or possibly descended from the aforementioned Sargon II, and appears to have been a charismatic figure attracting loyalty oaths from numerous other officials, including Aššur-nasir the chief eunuch touted by Kudurru as the coming king.6

Whether Kudurru had this quite right is questionable: A eunuch could not be a king. What he probably meant, then, was that Aššur-nasir would throw his support behind Sasî’s claim and serve as kingmaker. A fragment from a letter indicates that Sasî and Aššur-nasir were quite pally, with a spy notifying Esarhaddon that he had witnessed the pair at Calah agreeing to get rid of him before the next eclipse.7

Esarhaddon, understandably, was not a little perturbed at these revelations but could not decide what to do. He summoned his priests and demanded to know, “Will there be a rebellion against Esarhaddon” sometime within the next ninety days?

He needed to be thorough as he as yet had no true idea how far the conspiracy had spread outwards from Sasî and Aššur-nasir:

Will any of the eunuchs and the officials, the king’s entourage, or senior members of the royal line, or junior members of the royal line, or any relative of the kind whosoever, or the prefects, or the recruitment officers and team commanders, or the royal bodyguard, or his personal guard, or the king’s chariot men, or the keepers of the inner gates [of Nineveh], or the keepers of the outer gates, or the attendants of the mule stables, or the lackeys, or the cooks, confectioners, and bakers, the entire body of craftsmen, or the Ituens, the Elamites, the mounted bowmen, the Hittites and the Gureans, or the Akkadians, Arameans, or Cimmerians, or the Egyptians, or the Nubians, or the Qedarites, or their brothers, or their sons, or their nephews, of their friends, or their guests, or their accomplices, be they eunuchs or bearded, or any enemy at all, whether by day or by night, or in the city or in the country, whether while he is sitting on the royal throne, or in a chariot, or in a rickshaw, or while walking, whether while going out or coming in, . . . be it men who are on a miilitary assignment, or men who enter into or leave from tax-collection, or while he is eating or drinking, or girding or ungirding himself, or while engaged in washing himself, whether through deceit or guile . . . make an uprising and rebellion against Esarhaddon, king of Assyria? Will they act with evil intent against him.8

Unfortunately, we don’t know the answer for certain, as the priests’ reply has not yet been found.What we do know is that something spurred Esarhaddon into bloody action in 670. That year, “the king killed many of his magnates in Assyria with the sword,” as one chronicle calmly put it.

Kudurru’s fate is unknown, but he was likely liquidated during this purge of top government officials. A fragmentary piece of correspondence mentions tantalisingly that “Kudurru, son of Bel-[lost], an informer” was killed by one of the king’s bodyguards.9

I can’t imagine that Aššur-nasir, the dodgy chief eunuch, or his accomplice, the chief cupbearer Nabû-killanni, came out of this with their heads still attached.

As for the elusive Sasî, he seems to have holed up in Harran, along with the nameless slave-girl who had prophesied Esarhaddon’s death. We hear nothing more about them—all tangible sign of their existence was probably vengefully extirpated.

Careful of the Small Print

After the slaughter, much to Esarhaddon’s relief, the goddess Ishtar of Arbela revealed to a prophetess that “I will banish trembling from [your] palace. You [Esarhaddon] shall eat safe food and drink safe water, and you shall be safe in your palace. Your son and grandson shall rule as kings.”10

What got him in the end was the Delphic loophole in Ishtar’s pledge: “You shall be safe in your palace.” In 669, a year later, Esarhaddon embarked on a campaign to the Nile to put down yet another insurrection, and it was while he was absent from said palace—at Harran, spookily—that he died, naturally if suddenly.

And so too did his son Ashurbanipal reign gloriously from 669 to 631, and his grandson Ashur-etil-ilani (631-627), but the latter was weak and the Assyrian Empire was on its last legs. Within a few years of Ashur’s death, the Medes and the Babylonians sacked Nineveh, and all the secrets of intrigues past contained in Ashurbanipal’s library vanished for two and a half millennia.

Further Reading: G. Brereton, I am Ashurbanipal: King of the World, King of Assyria (Thames & Hudson, 2020); D. Damrosch, The Buried Book: The Loss and Rediscovery of the Great Epic of Gilgamesh (New York, 2006); I. Finkel, The Ark Before Noah: Decoding the Story of the Flood (Anchor, 2015); S. Helle (trans.), Gilgamesh: A New Translation of the Ancient Epic (Yale University Press, 2021); K. Radner, “The Trials of Esarhaddon: The Conspiracy of 670 B.C.,” Isimu, 6 (2003), pp. 165-84.

On Arda-Mullissi, see letter, “Your Son Will Kill You!,” in F. Reynolds (ed.), The Babylonian Correspondence of Esarhaddon and Letters to Assurbanipal and Sin-šarru-iškun from Northern and Central Babylonia (State Archives of Assyria, 2003), 18, No. 100, at http://oracc.org/saao/P236909/.

Letter, “Will the Chief Eunuch Take Over the Kingship?,” in S. Parpola (ed.), Letters from Assyrian and Babylonian Scholars (State Archives of Assyria, 1993), 10, No. 179, at http://oracc.org/saao/P237270/.

Letter, “The Conspiracy of Sasî,” in M. Luukko and G. Van Buylaere (eds.), The Political Correspondence of Esarhaddon (State Archives of Assyria, 2002), 16, No. 59, at http://oracc.org/saao/P313533/.

See letter, “More on the Conspiracy of Sasî,” ibid., No. 60, at http://oracc.org/saao/P313432/, which refers to courtiers and officials being in league with each other, mentions the chief eunuch, and notes that they are “making a rebellion.”

Note, “Babylonians Working in the Library,” in F.M. Fales and J.N. Postgate (eds.), Imperial Administrative Records, Part II: Provincial and Military Administration (State Archives of Assyria, 1995), 11, No. 156, at http://oracc.org/saao/P334311/.

There’s a letter fragment mentioning a Sasî as “the superintendent of the crown prince”—perhaps some kind of seer, counselor, or tutor—but it’s difficult to confirm whether this is the same one. See Luukko and Van Buylaere (eds.), Political Correspondence of Esarhaddon, No. 69, at http://oracc.org/saao/P334309/.

Letter, “Events Preceding the Enthronement of a Substitute King,” in Parpola (ed.), Letters from Assyrian and Babylonian Scholars, No. 377, at http://oracc.org/saao/P334672/.

Letter, “Will There Be a Rebellion Against Esarhaddon?,” in I. Starr (ed.), Queries to the Sungod: Divination and Politics in Sargonid Assyria (State Archives of Assyria, 1990), 4, No. 139, at http://oracc.org/saao/P336086/. I’ve simplified the text a little.

Letter, “Hemerology for Month Iyyar,” in H. Hunger ed.), Astrological Reports to Assyrian Kings (State Archives of Assyria, 1992), 8, No. 567, at http://oracc.org/saao/P238089/.

“Oracles of Encouragement to Esarhaddon,” in S. Parpola ed.), Assyrian Prophecies (State Archives of Assyria, 1997), 9, No. 1, at http://oracc.org/saao/P333952/.